11 Beam Deflection

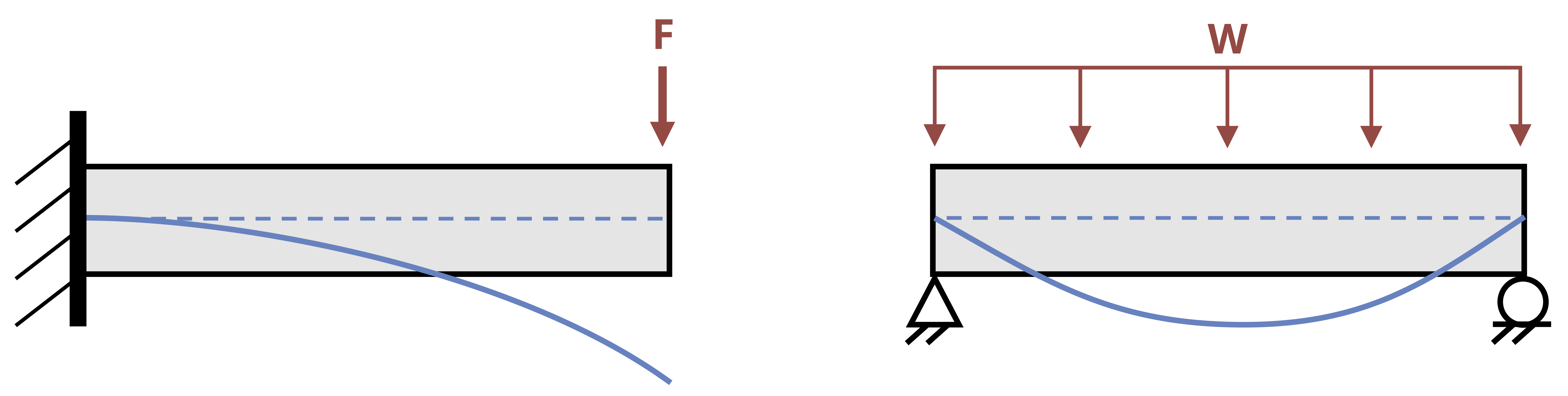

We now know how to calculate both the bending stress (Chapter 9) and shear stress (Chapter 10) in a beam. This chapter considers the deformation of a beam subjected to bending and shear stresses. Under load, beams deflect from their original position (Figure 11.1). Some amount of deflection is unavoidable, but it is usually desirable to limit deflection as much as possible. Although deflection often pose no safety risk (unless the allowable stress of the beam is also exceeded), too much deflection can render a beam unfit for purpose.

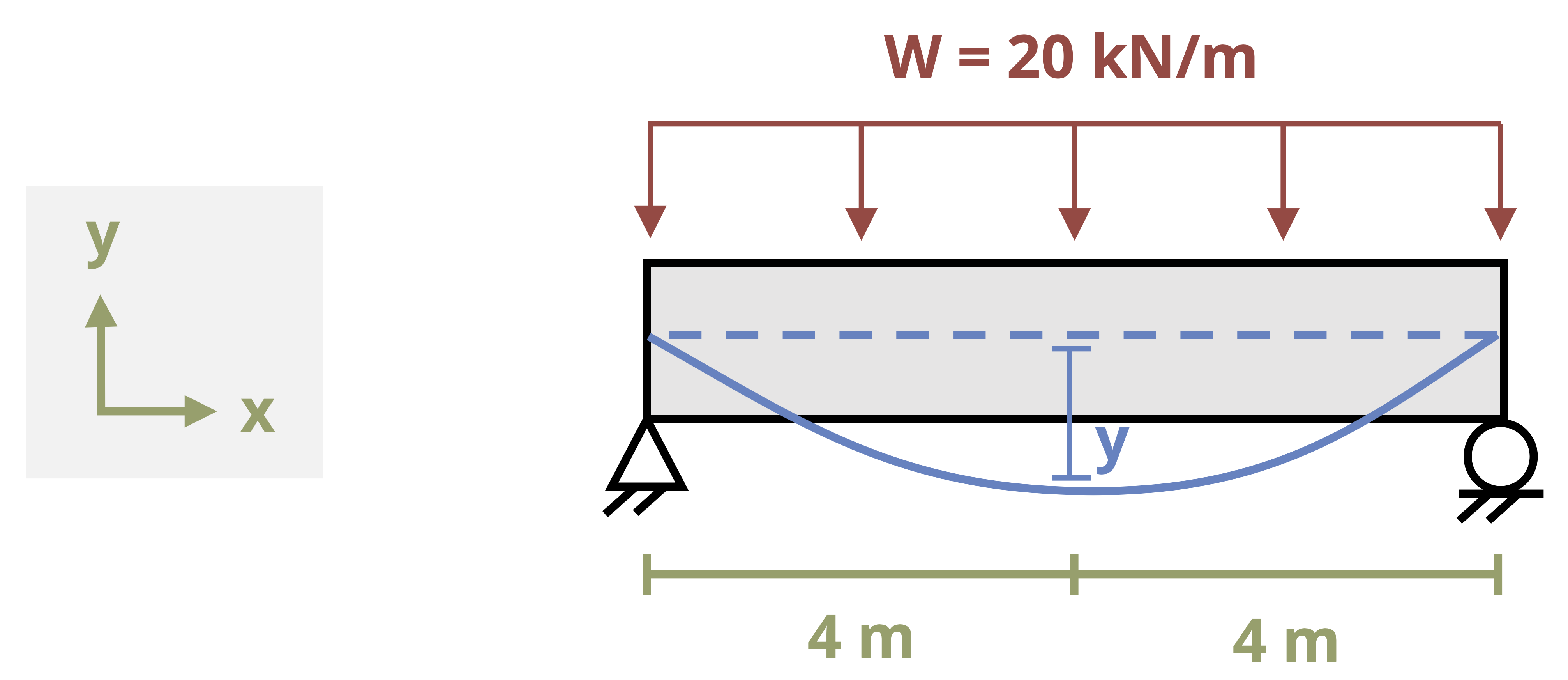

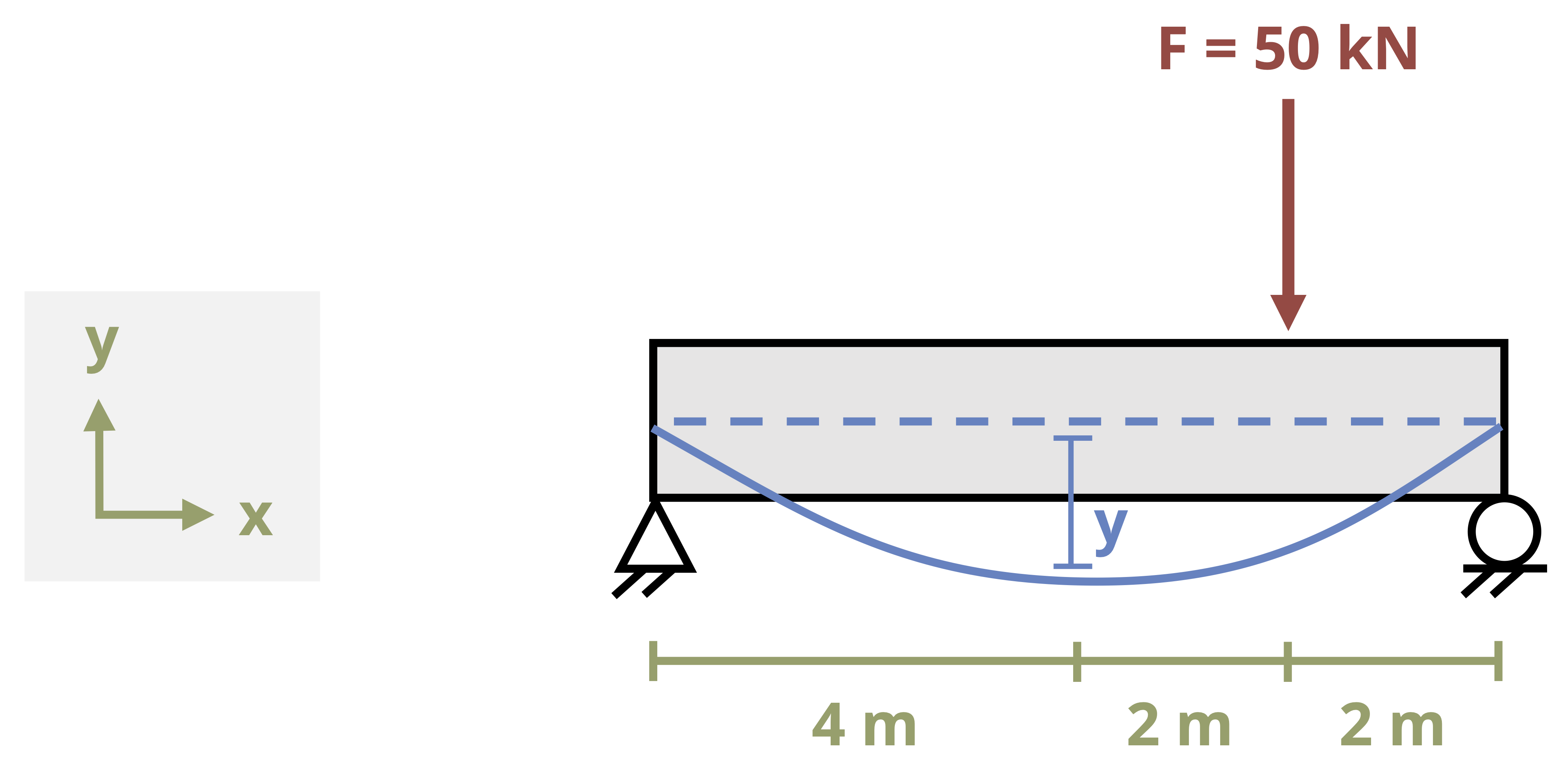

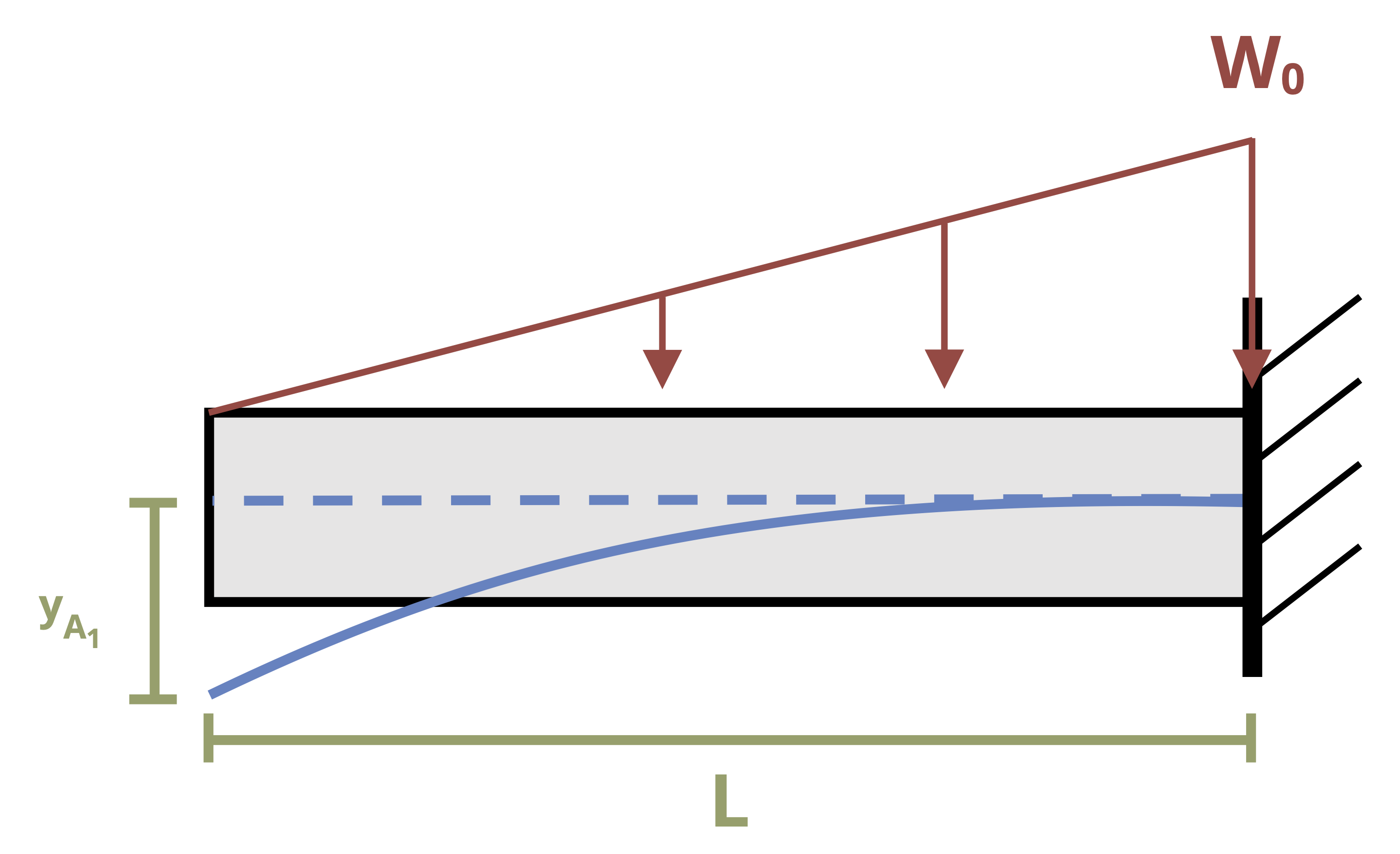

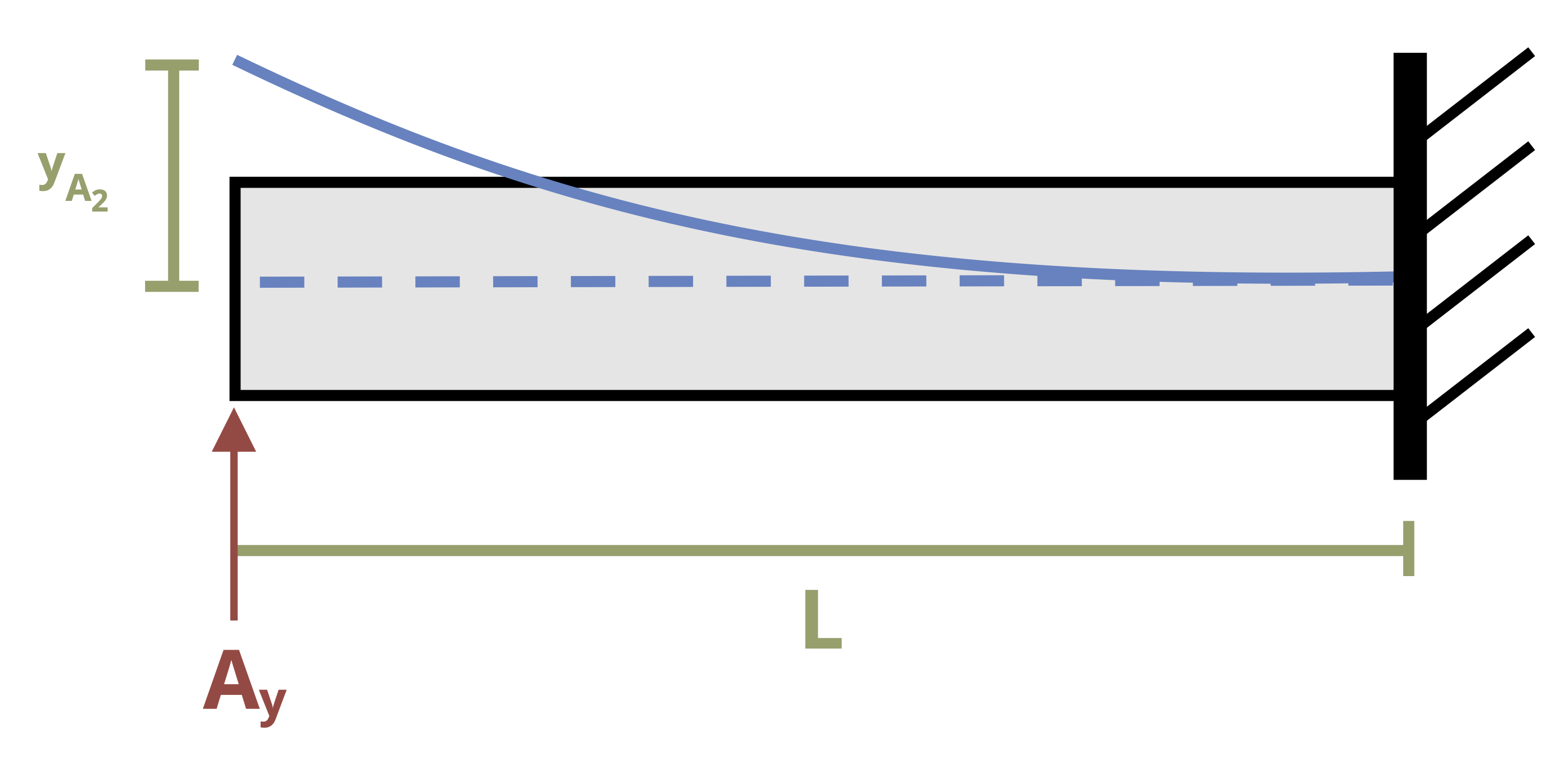

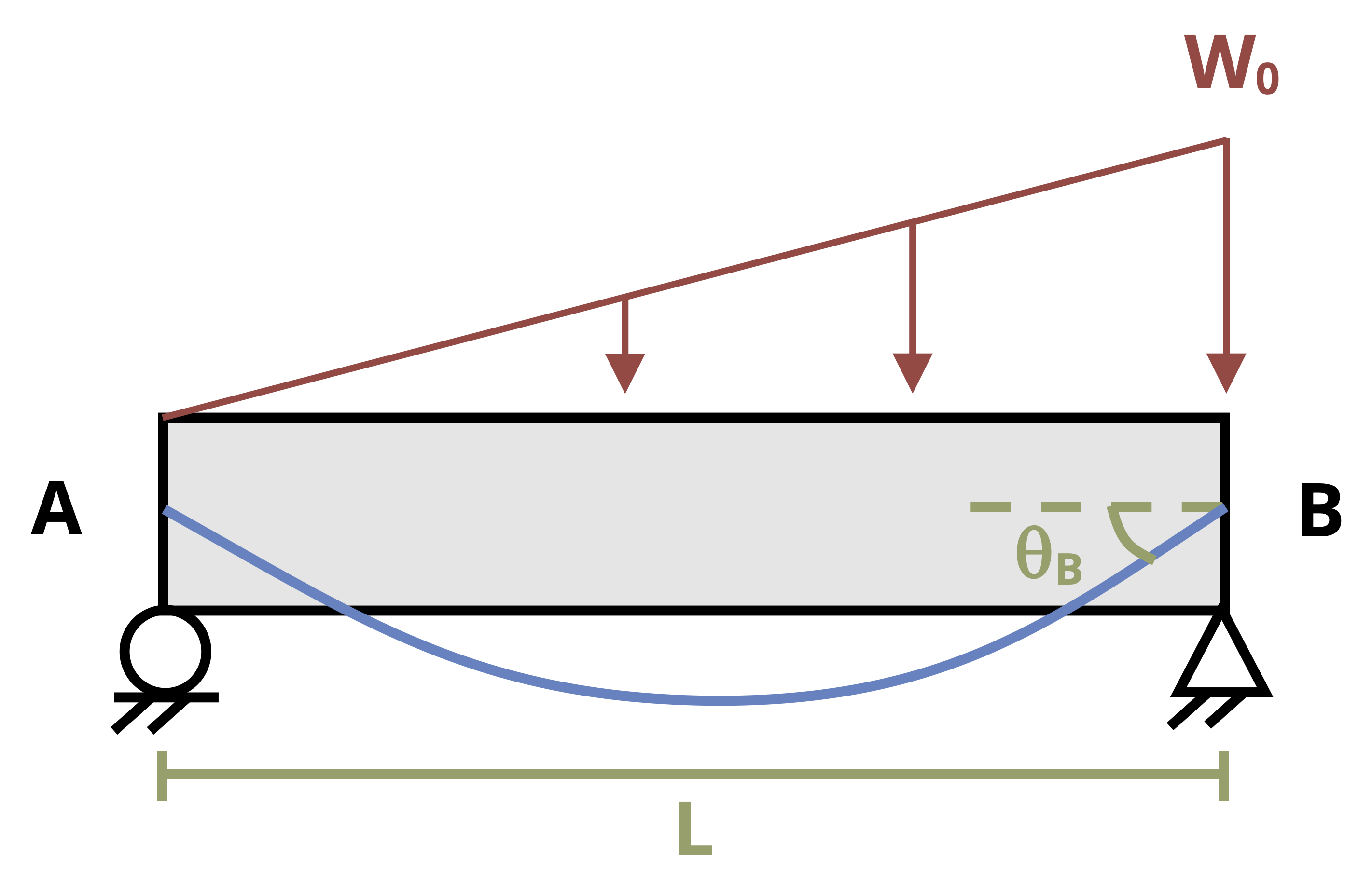

The deflected shape of the beam is known as the elastic curve (Figure 11.2). Exaggerated sketches of the elastic curve provide a quick visual reference of how the beam will deflect and can be used to check that our numerical answers are realistic.

Section 5.3 showed us how to calculate deformation due to axial load \(\left(\Delta L=\frac{F L}{A E}\right)\). Section 6.2 showed us how to calculate deformation due to torsional load \(\left(\varnothing=\frac{T L}{J G}\right)\). Recall that both types of deformation depend on these elements:

Applied/internal load (F, T)

Length of the object (L)

Cross-section geometry (A, J)

Material properties (E, G)

It is probably unsurprising, then, that beam deflection also depends on these four elements.

This chapter introduces two common techniques for calculating deflection: the method of integration (Section 11.1 and Section 11.2) and the method of superposition (Section 11.3).

Being able to calculate deflection is vitally important because it allows us to predict how much a beam will deflect before we build a structure. Additionally, being able to calculate deflection will help us solve some more statically indeterminate problems (Section 11.4).

Finally, Section 11.5 enables us to build on our beam design work of Section 9.2 by expanding the specifications to include limitations on shear stress and deflection as well as bending stress.

11.1 Integration of the Moment Equation

Click to expand

We’ll begin by deriving an equation for calculating the deflection at any point in a loaded beam. In Section 9.1 we derived equations relating to bending strain and bending stress.

\[ \varepsilon=-\frac{y}{\rho} \]

\[ \sigma=-\frac{My}{I} \]

Applying Hooke’s law to the strain equation produces

\[ \begin{aligned} \varepsilon=-\frac{y}{\rho}&=\frac{\sigma}{E} \\ \sigma&=-\frac{Ey}{\rho} \end{aligned} \]

Setting the two stress equations equal produces

\[ \frac{E y}{\rho}=\frac{M y}{I} \]

Then rearranging the result yields

\[ \frac{1}{\rho}=\frac{M(x)}{E I} \]

The radius of curvature (ρ) can be related to the deflection (y) by the equation

\[ \frac{1}{\rho}=\frac{\frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}}}{\left[1+\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)^{2}\right]^{\frac{3}{2}}} \]

This equation describes the exact deflection \((y)\) at any distance \((x)\) along the beam for elastic deformations. In most engineering applications the deflection \((y)\) is very small. We can simplify this equation significantly by assuming that the deflection \((y)\) will be small and thus that \(\frac{d y}{d x}\) is very small and \(\left(\frac{d y}{d x}\right)^{2}\) is negligible. This simplifies the equation to

\[ \frac{1}{\rho}=\frac{\frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}}}{[1+0]^{\frac{3}{2}}}=\frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}} \]

Finally, the equation becomes

\[ \frac{1}{\rho}=\frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}}=\frac{M(x)}{E I} \]

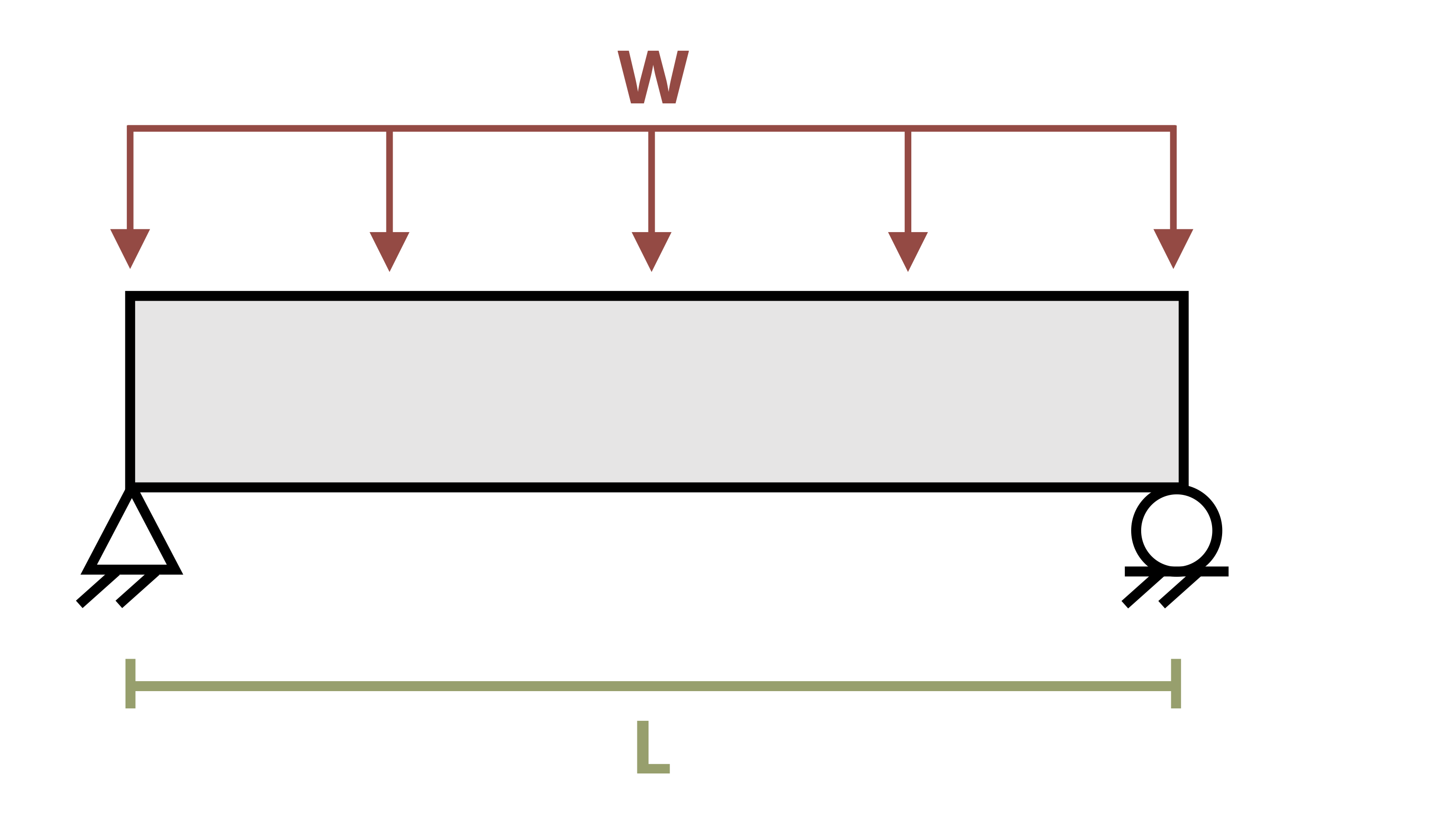

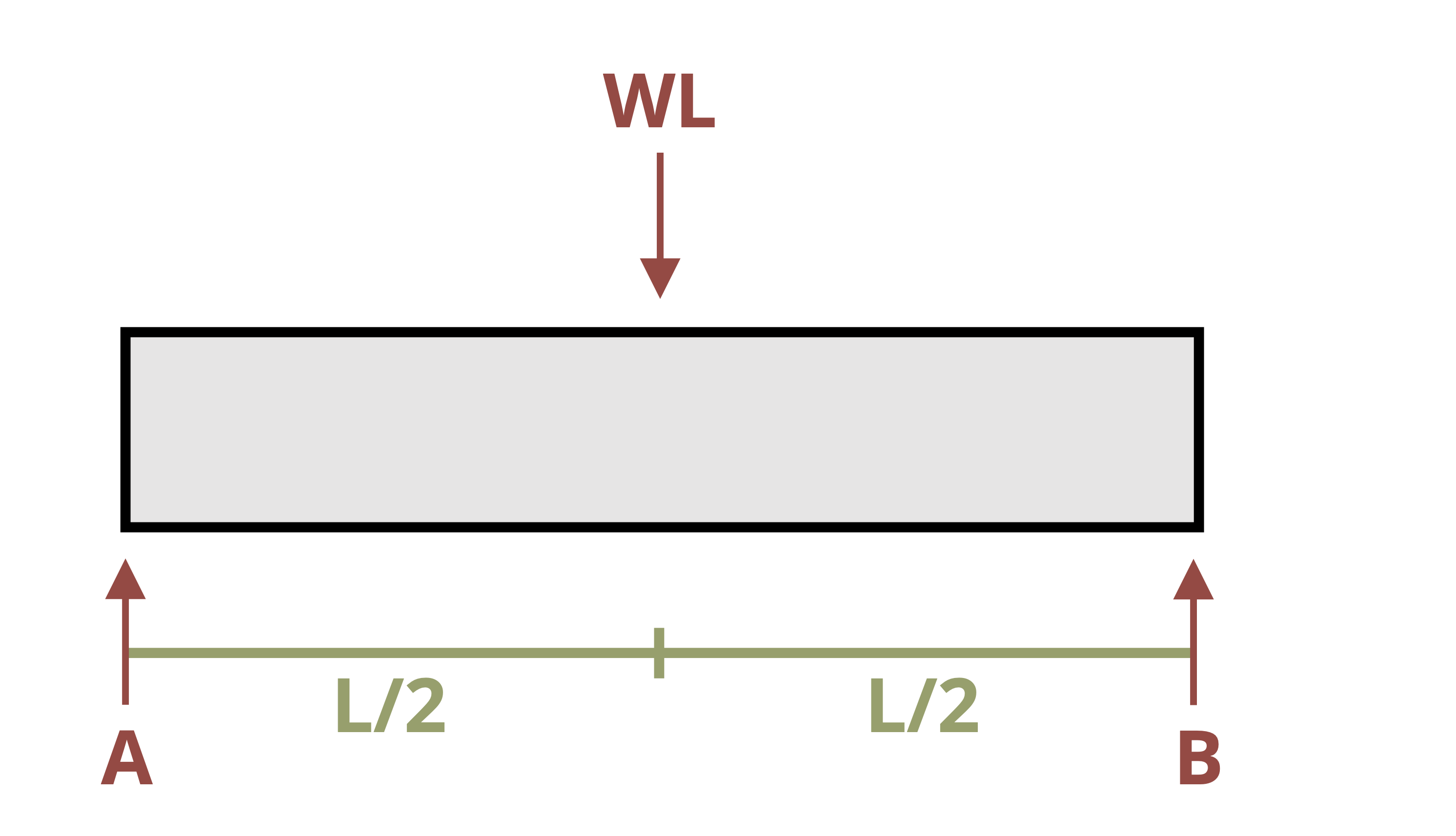

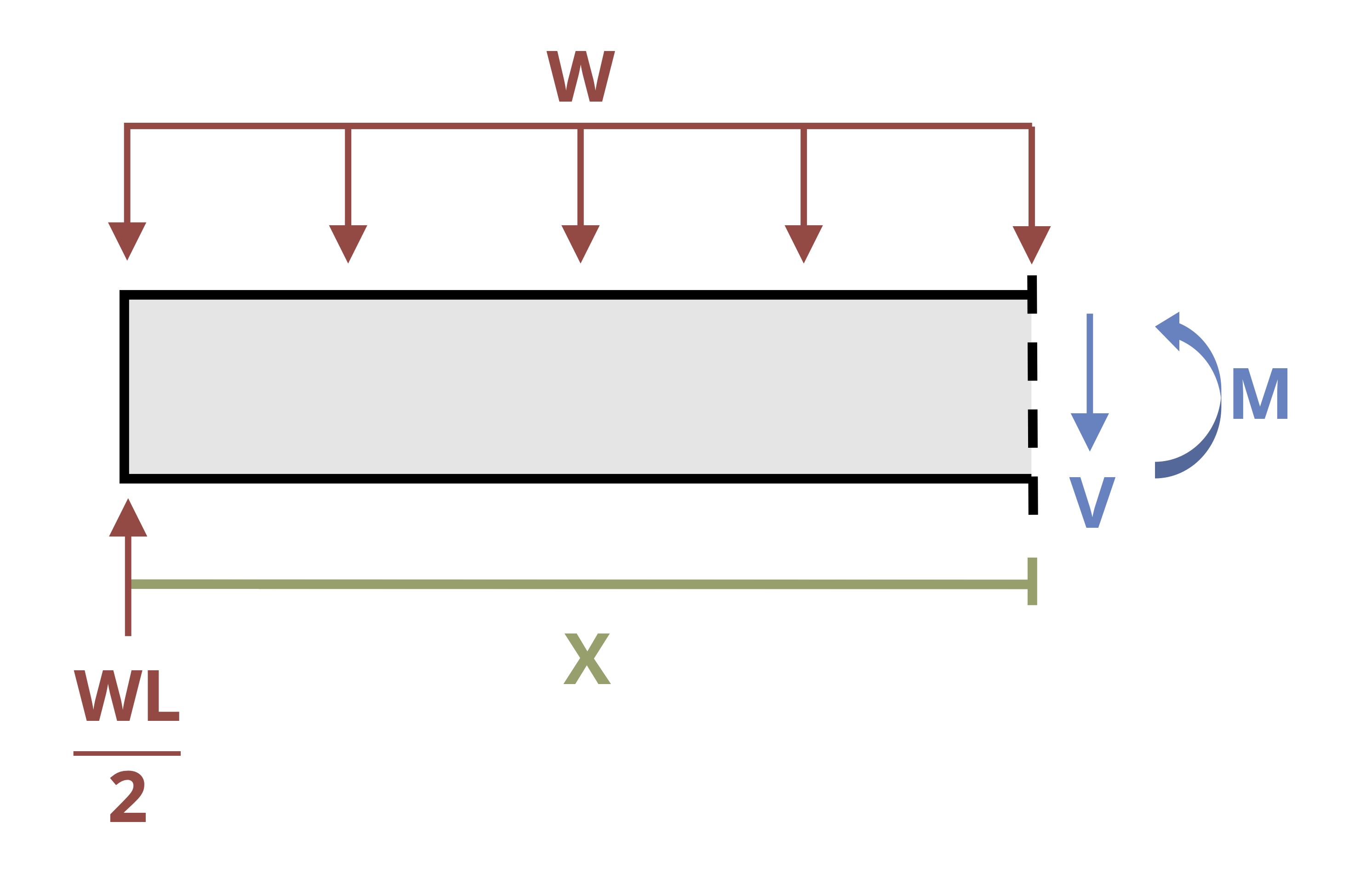

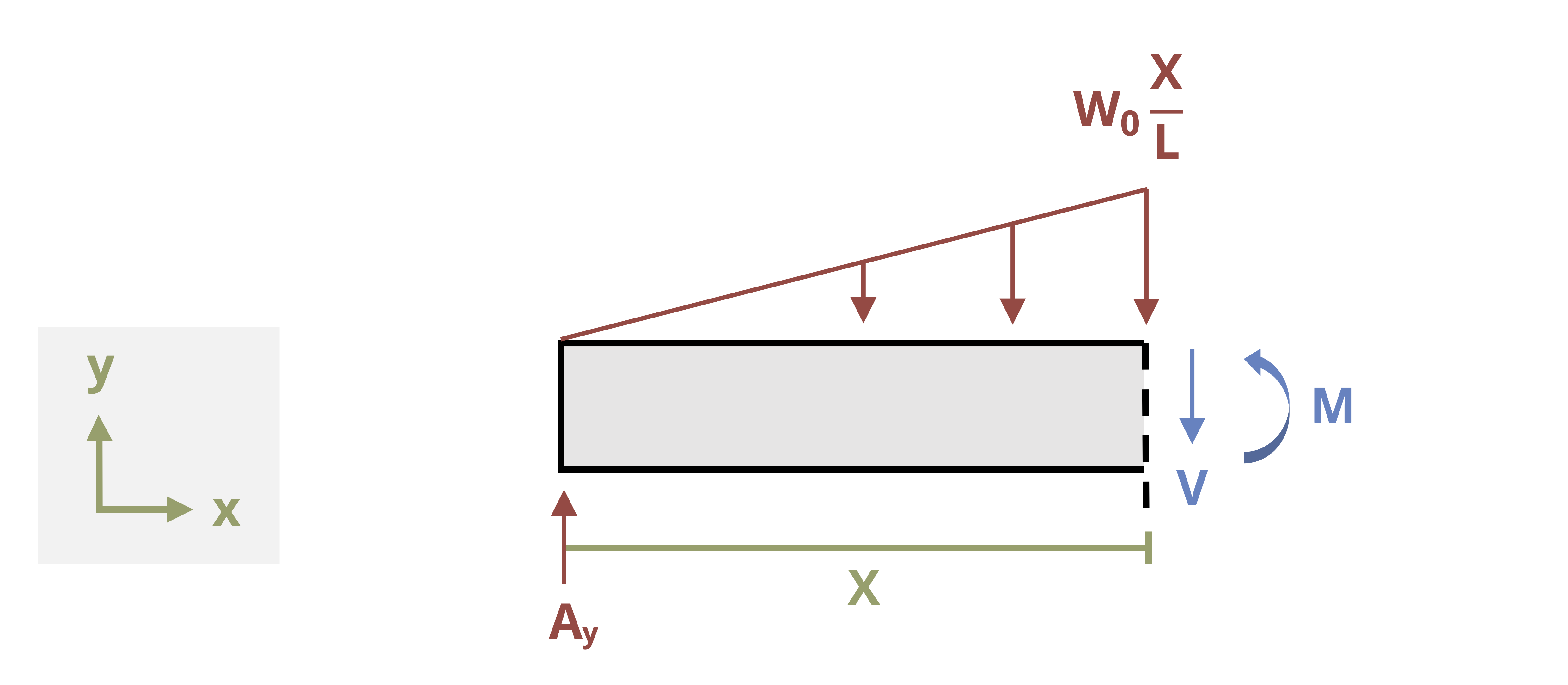

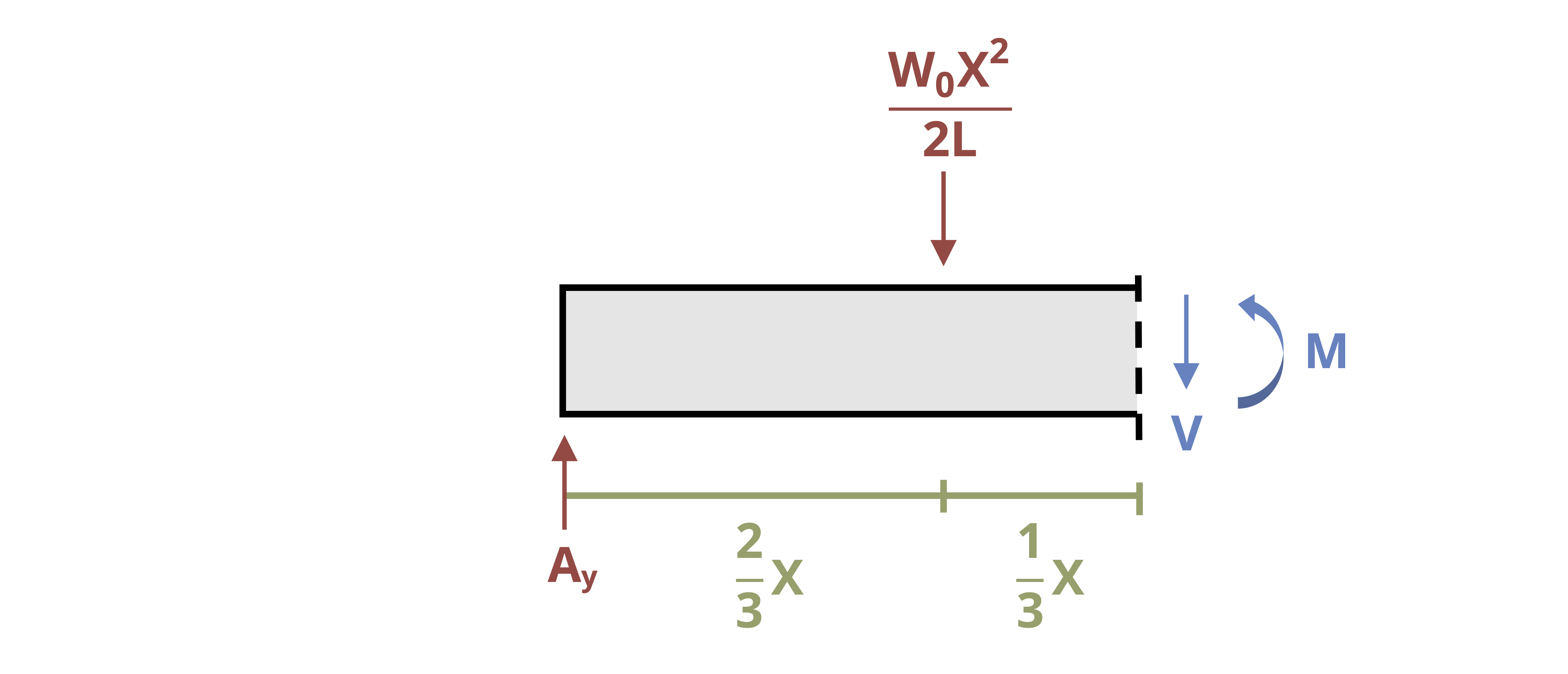

To solve for deflection first find an equation for the internal bending moment as a function of \((x)\), using equilibrium just as in Section 7.3 for drawing the bending moment diagram. Then set this equation equal to \(E I \frac{d^{2} y}{d x^{2}}\) and integrate twice.

\[ \boxed{\begin{gathered} M(x)=E I \frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}} \\ \int M(x) d x+C_1=E I \frac{\partial y}{\partial x} \\ \iint M(x) d x+C_1 x+C_2=E I y \end{gathered}} \tag{11.1}\]

In these equations \(y\) represents the deflection of the beam and \(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\) represents the slope of the deflected beam. Since the equations are functions of \(x\), we can find the slope and deflection at any point along the beam.

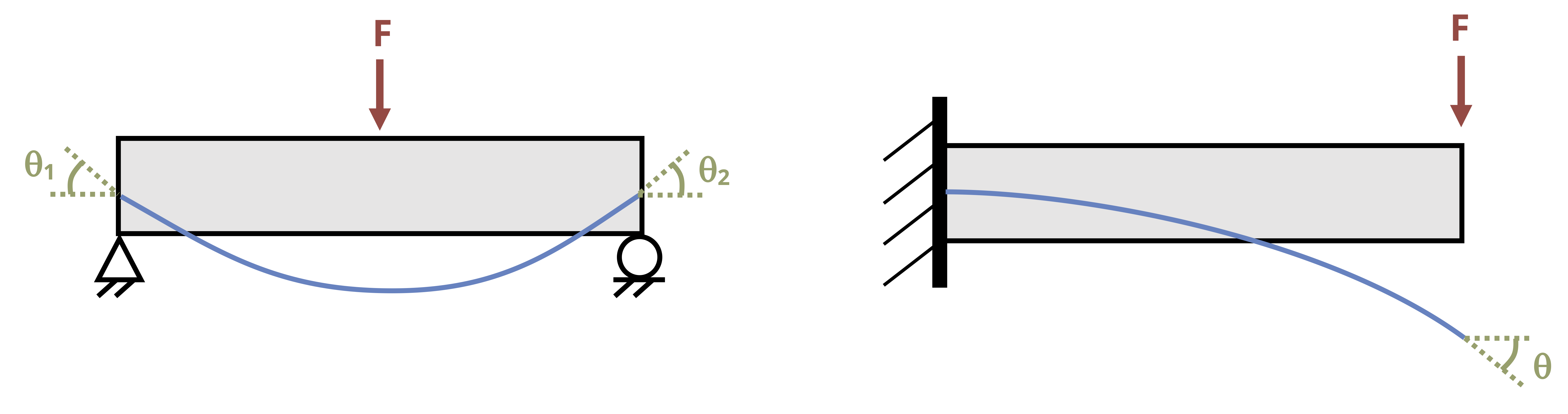

Note that each successive integral introduces a constant of integration that we must solve for. We do this through the use of boundary conditions—that is, points on the beam where we already know the slope and/or deflection. There are two common boundary conditions for our applications:

At any support the deflection \((y)\) is zero.

At a fixed support the slope \(\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)\) is zero.

Figure 11.3 illustrates these boundary conditions. Once the constants of integration are known, we can define equations for the slope and deflection of the beam in terms of distance \((x)\) along the beam and calculate the slope and deflection at any value of \(x\). Example 11.1 and Example 11.2 show this process applied to a simply supported beam and a cantilever beam respectively.

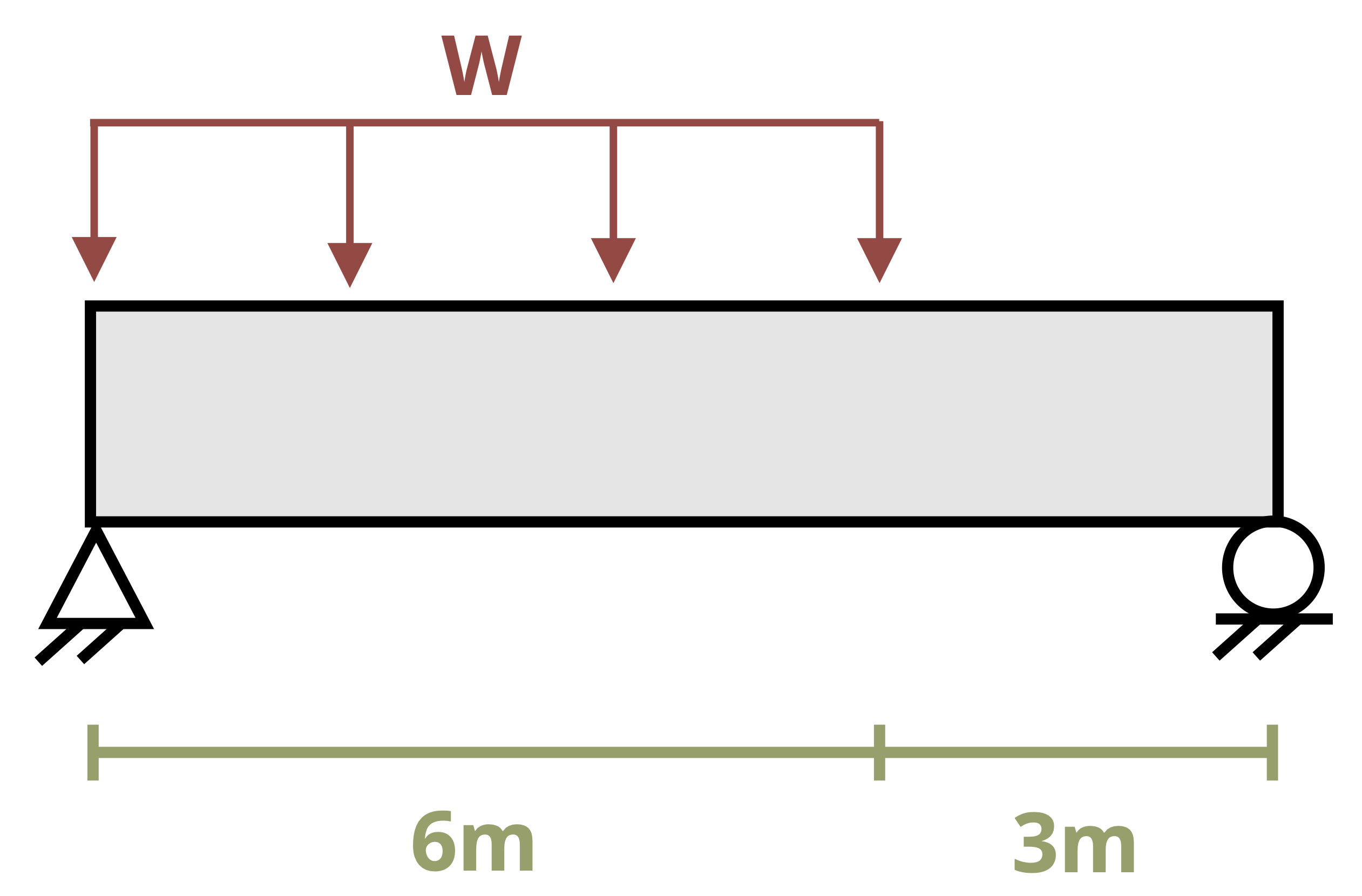

These examples have single continuous loads. If the loading is discontinuous, however, we must modify our approach because no single moment equation can describe the entire beam. Section 7.3 showed that when drawing shear force and bending moment diagrams we can find a different equation for the internal bending moment in each loading region (i.e., a piecewise function over the length of the beam). This requires finding separate moment equations for each loading region and integrating each separately. Do this each time the loading changes, considering

Both sides of a concentrated load

A distributed load that begins or ends

This text covers deflection of beams made of a single material with uniform cross-sections (i.e., where elastic modulus, E, and second moment of area, I, remain constant). In practice, changes in E and I necessitate additional separate equations for each change.

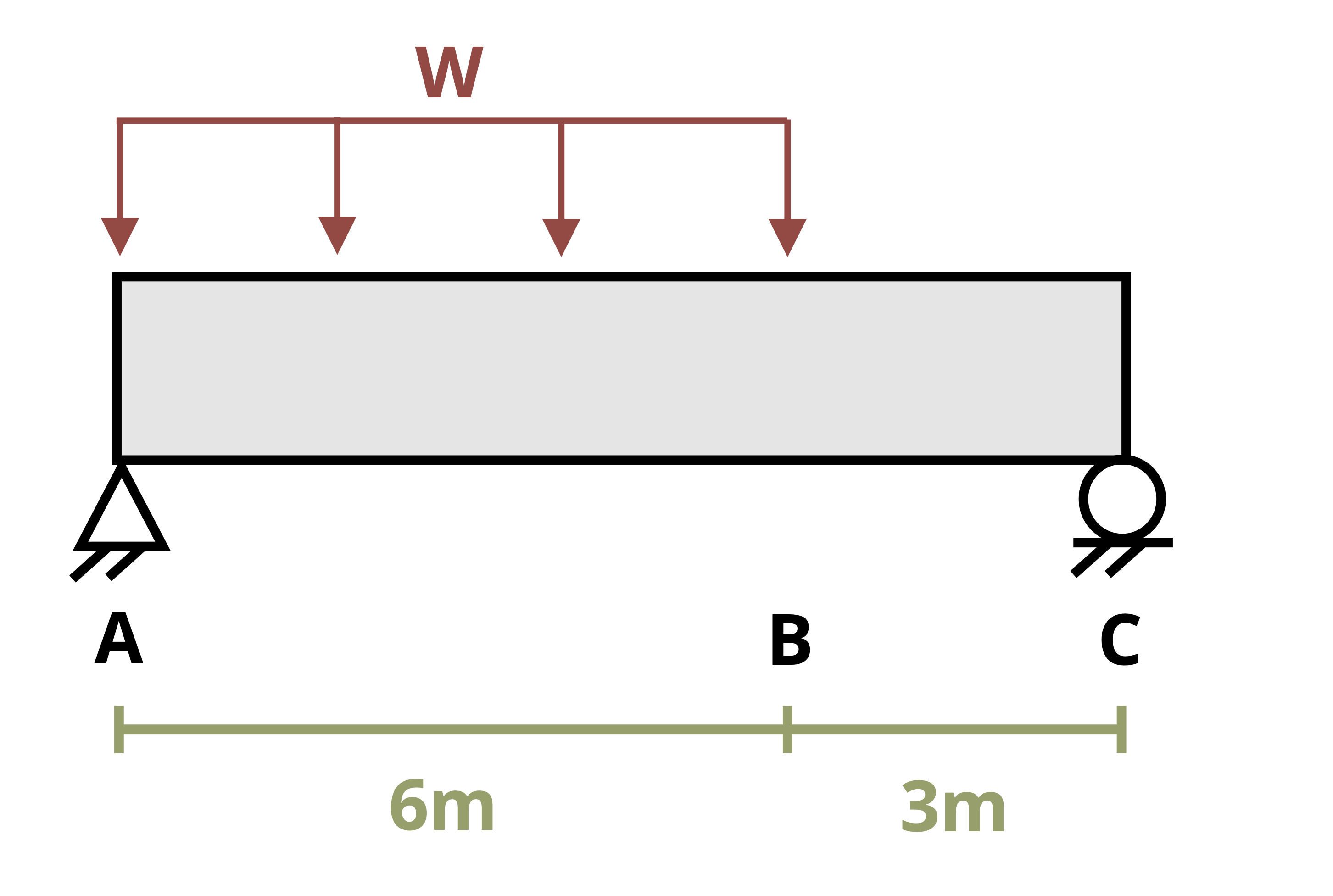

Figure 11.4 shows a beam with two loading regions. Fully describing the deflection in this beam requires us to determine two internal bending moment equations—one in segment AB and one in segment BC. Each equation must be integrated twice, thereby introducing four constants of integration. Although two of these can be determined by using boundary conditions, we must determine the remaining two by using continuity conditions.

Equation set 1 describes the internal moment, slope, and deflection of the beam from point A to point B, and equation set 2 describes the internal moment, slope, and deflection from point B to point C. Note that both sets of equations describe point B, where the loading changes. They must therefore return the same results at point B. So we can say that

\[ \begin{aligned} \left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{1} & =\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{2} \\ y_{1} & =y_{2} \end{aligned} \]

See Example 11.3 for the full solution for this beam.

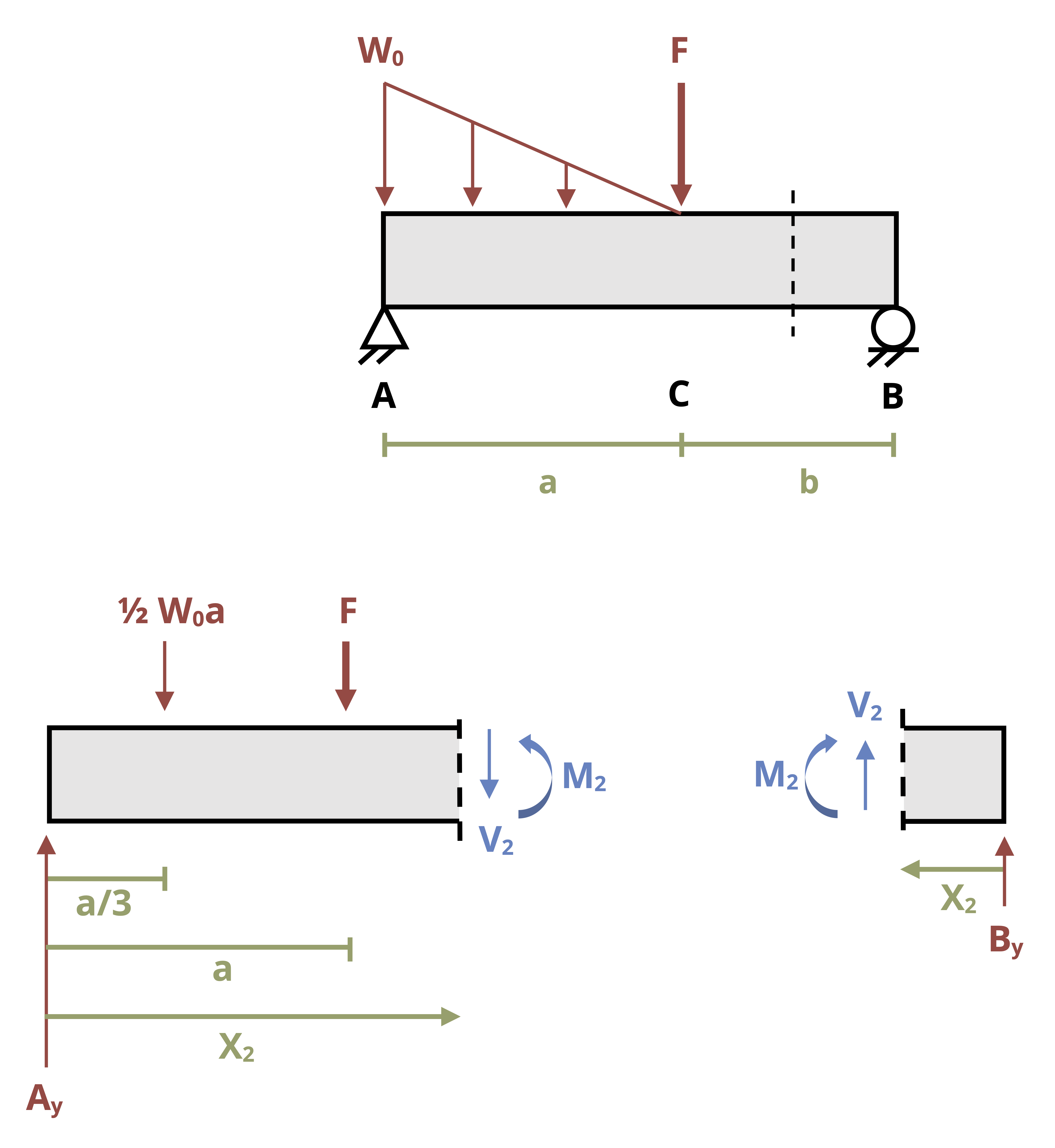

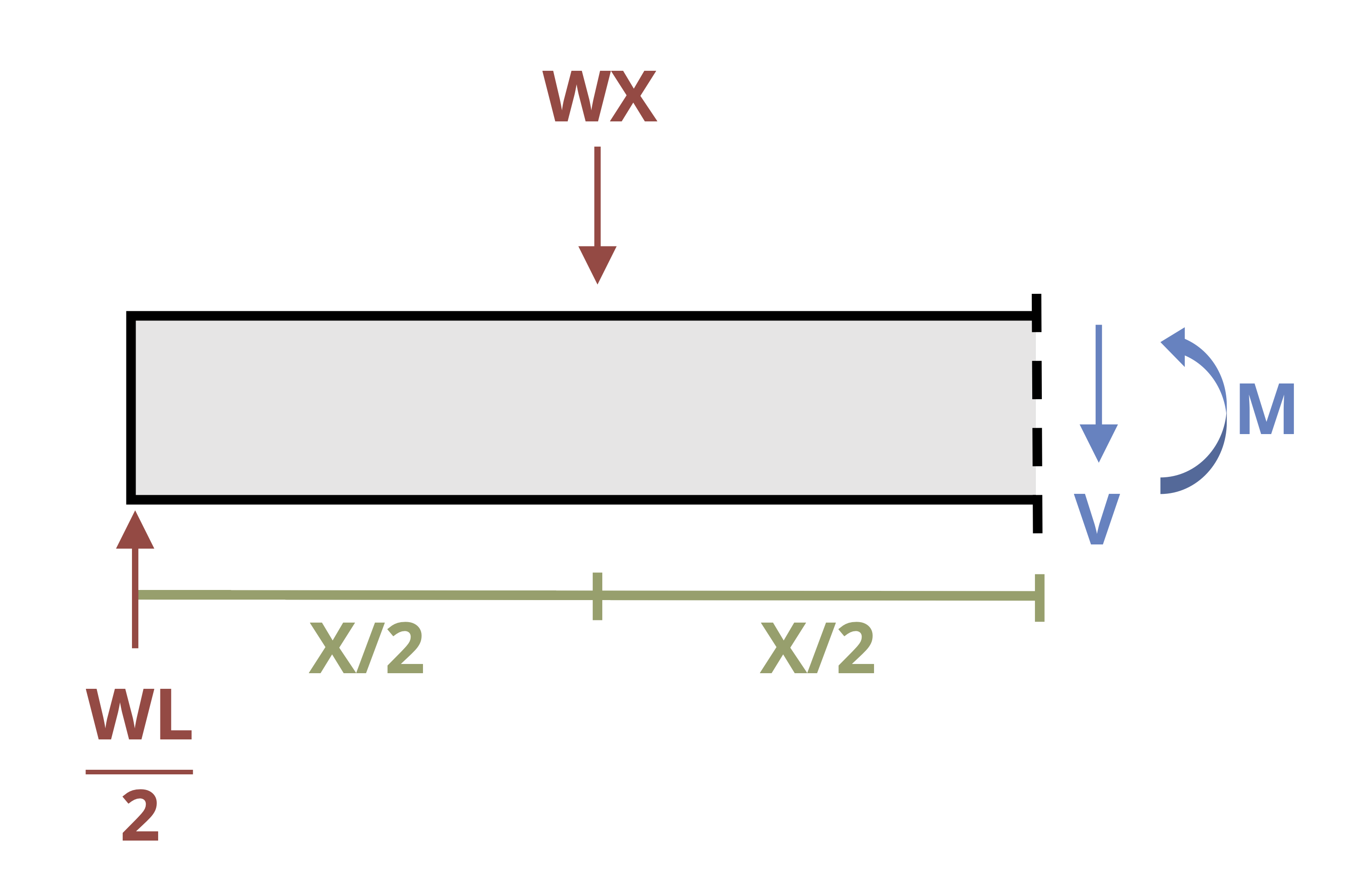

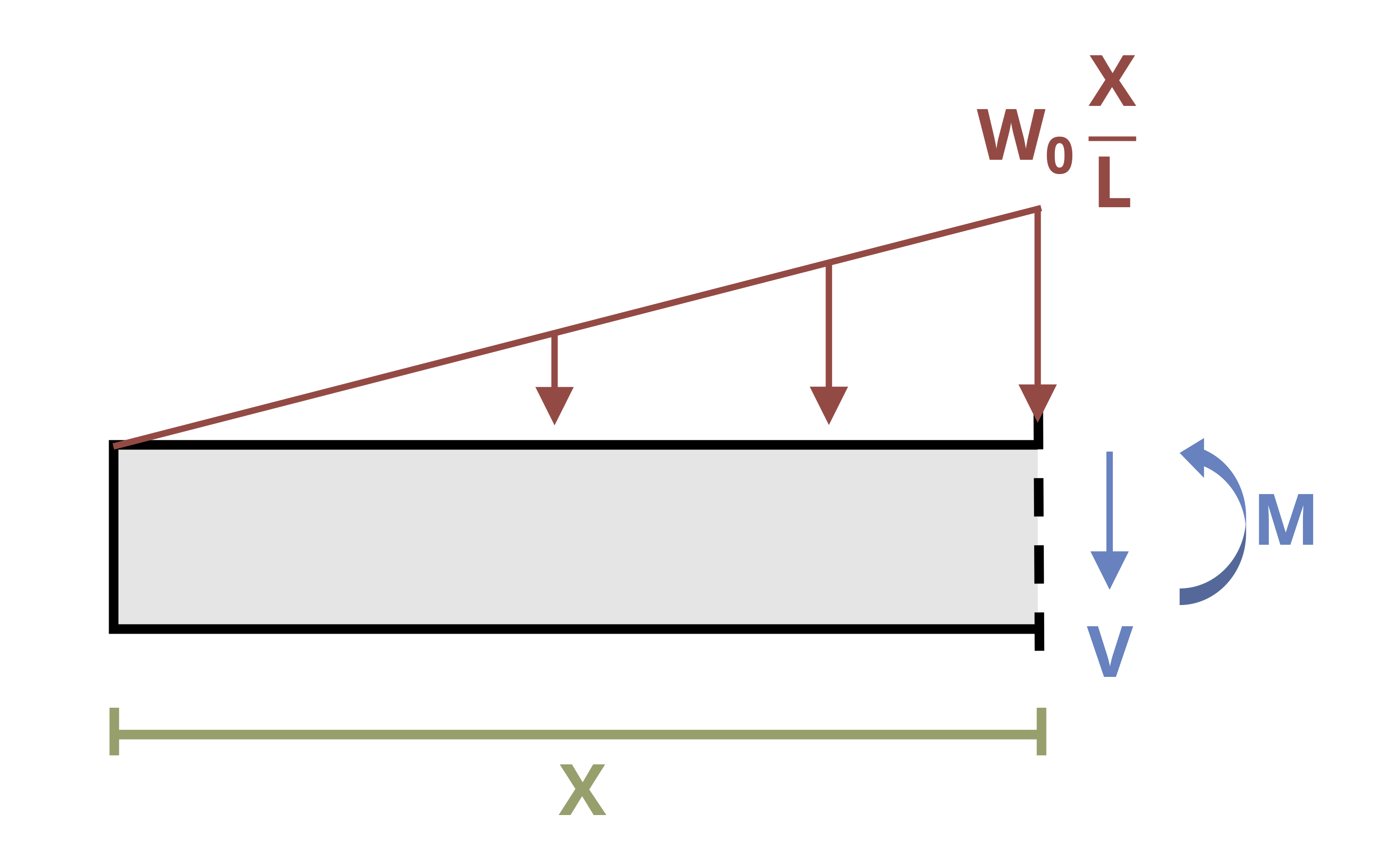

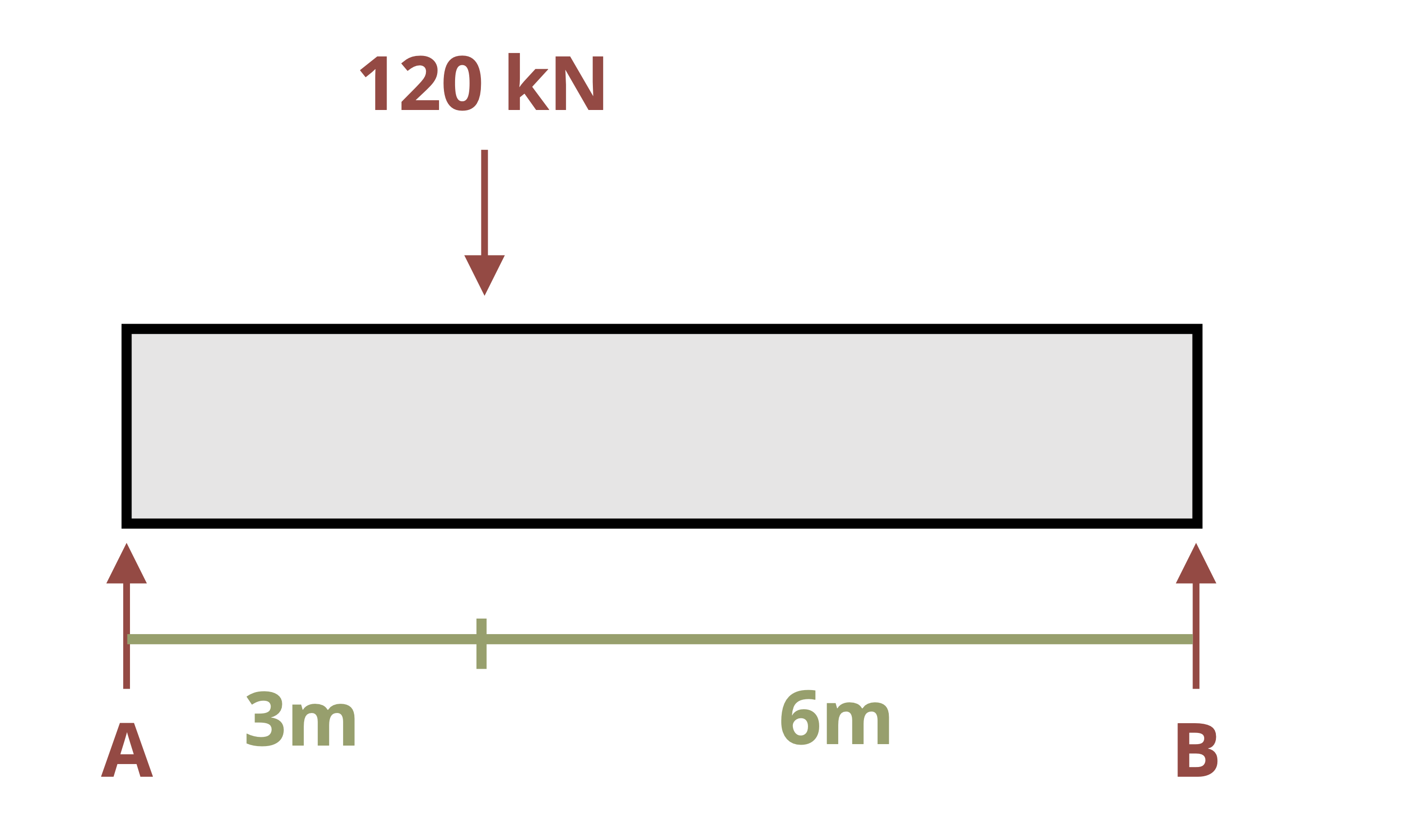

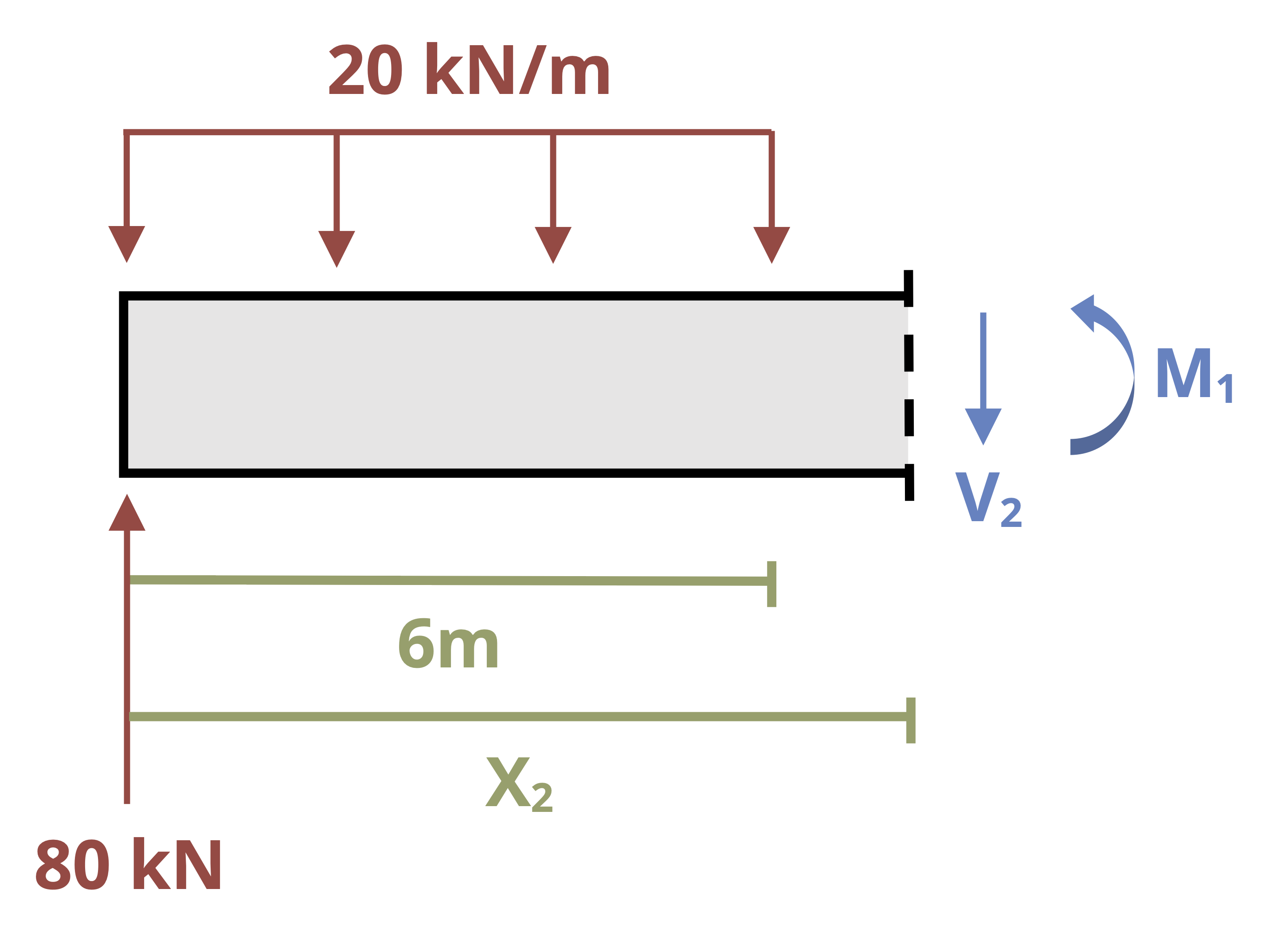

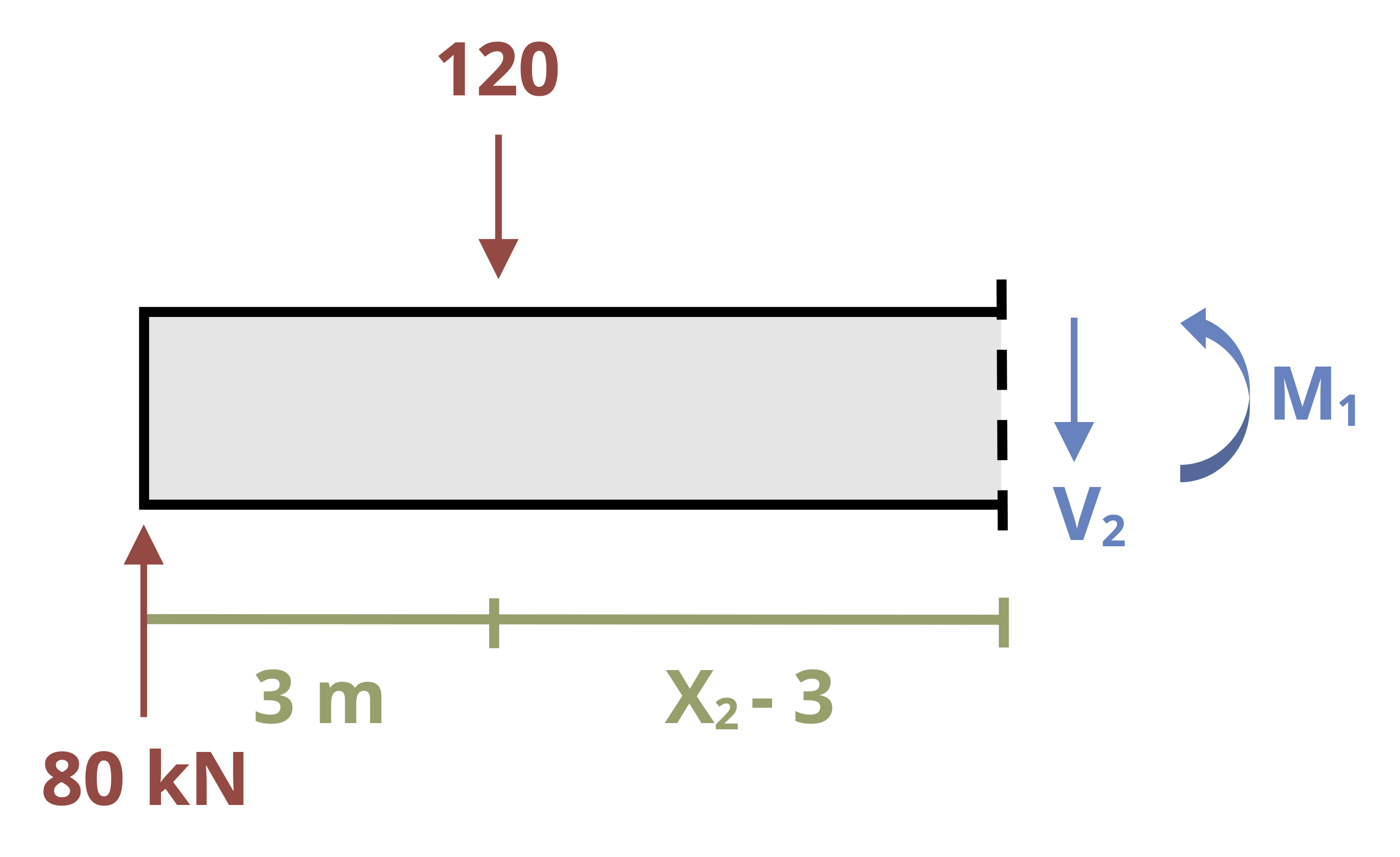

Note that we are not required to make both cuts from the left to find the internal bending moment. In some cases making one cut from the left and the other from the right may be the easier approach. Consider the beam in Figure 11.5. Given a cut in the region not under the distributed load, an FBD of the left side of the cut shows many more forces than an FBD of the right side.

The moment equation is less complex if we draw the right-hand side of the cut rather than the left-hand side. This in turn simplifies the integrations and the math involved in finding the constants of integration.

If, however, we do measure distance x2 from the right, we must make one change to the continuity conditions. Recall that when both cuts are from the left, at point C the slope and deflection calculated from equation 1 must be the same as those calculated from equation 2.

\[ \begin{aligned} \left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{1} & =\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{2} \\ y_{1} & =y_{2} \end{aligned} \]

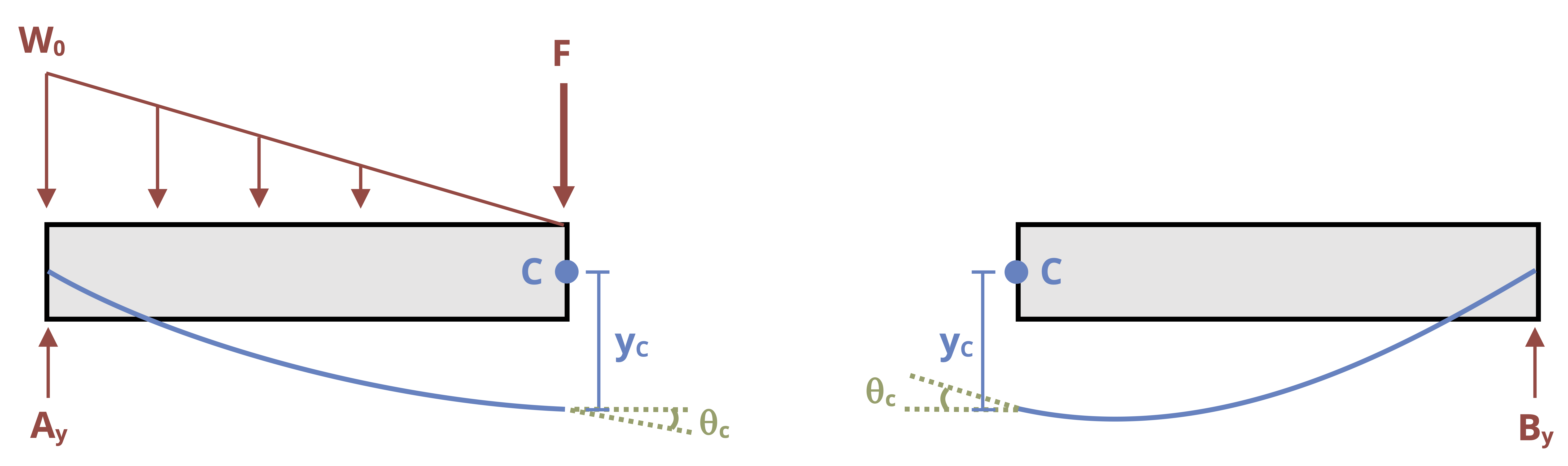

When distance x2 is measured from the right, \(y_1 = y_2\) at point C because the deflection is downward whether we measure the horizontal distance from the left or from the right. The magnitude of the slope will also be the same at point C regardless of which equation we use to calculate it. However, the direction of rotation of the slope will change from counterclockwise to clockwise because we have changed the coordinate system (Figure 11.6). Thus our second boundary condition must become

\[ \left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{1}=-\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{2} \]

This negative sign is vitally important, and we will not obtain the correct answer if we forget to include it. Example 11.3 has been reworked, this time with one cut made from the right-hand side. Compare this with the previous solution to see the differences.

11.2 Integration of the Load Equation

Click to expand

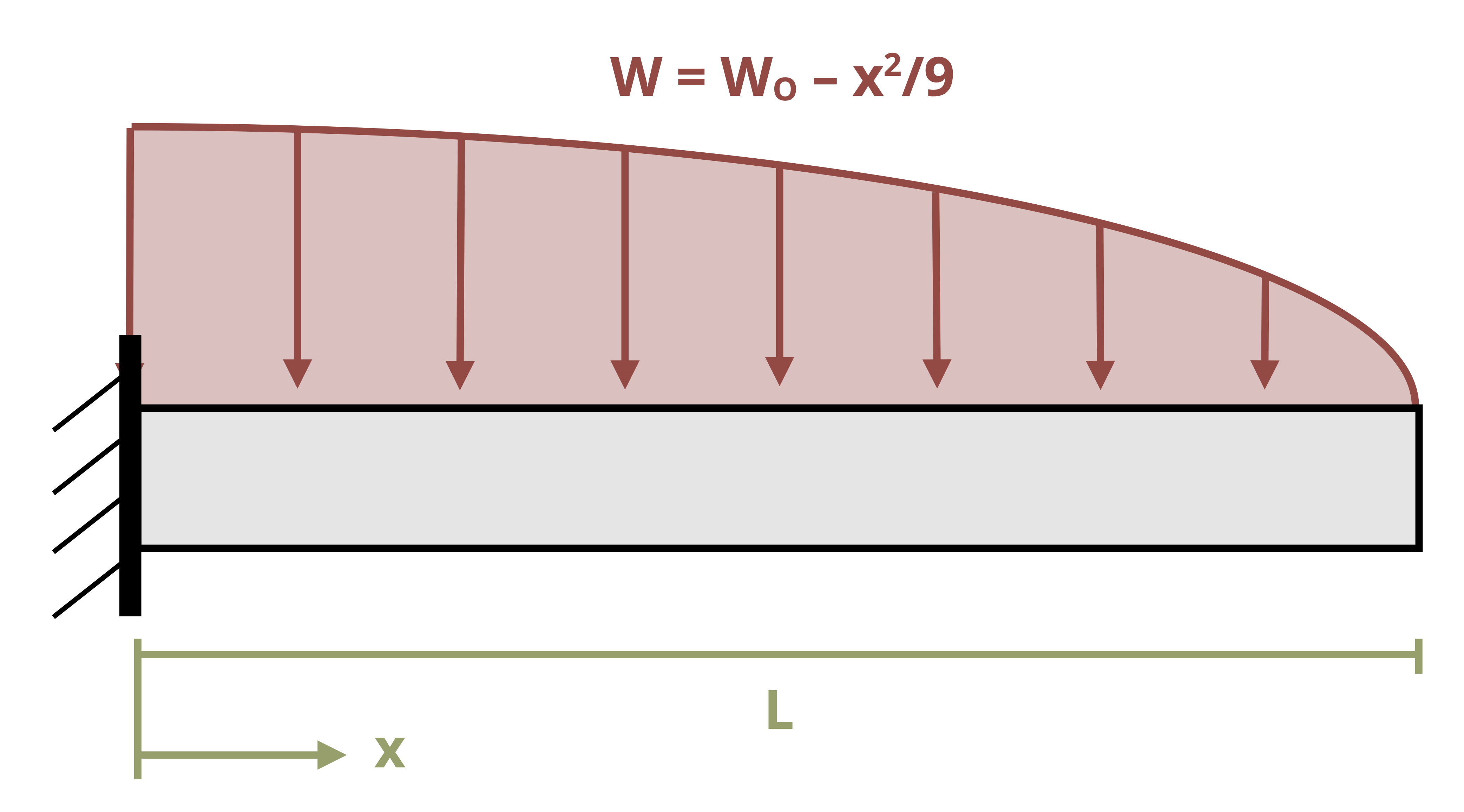

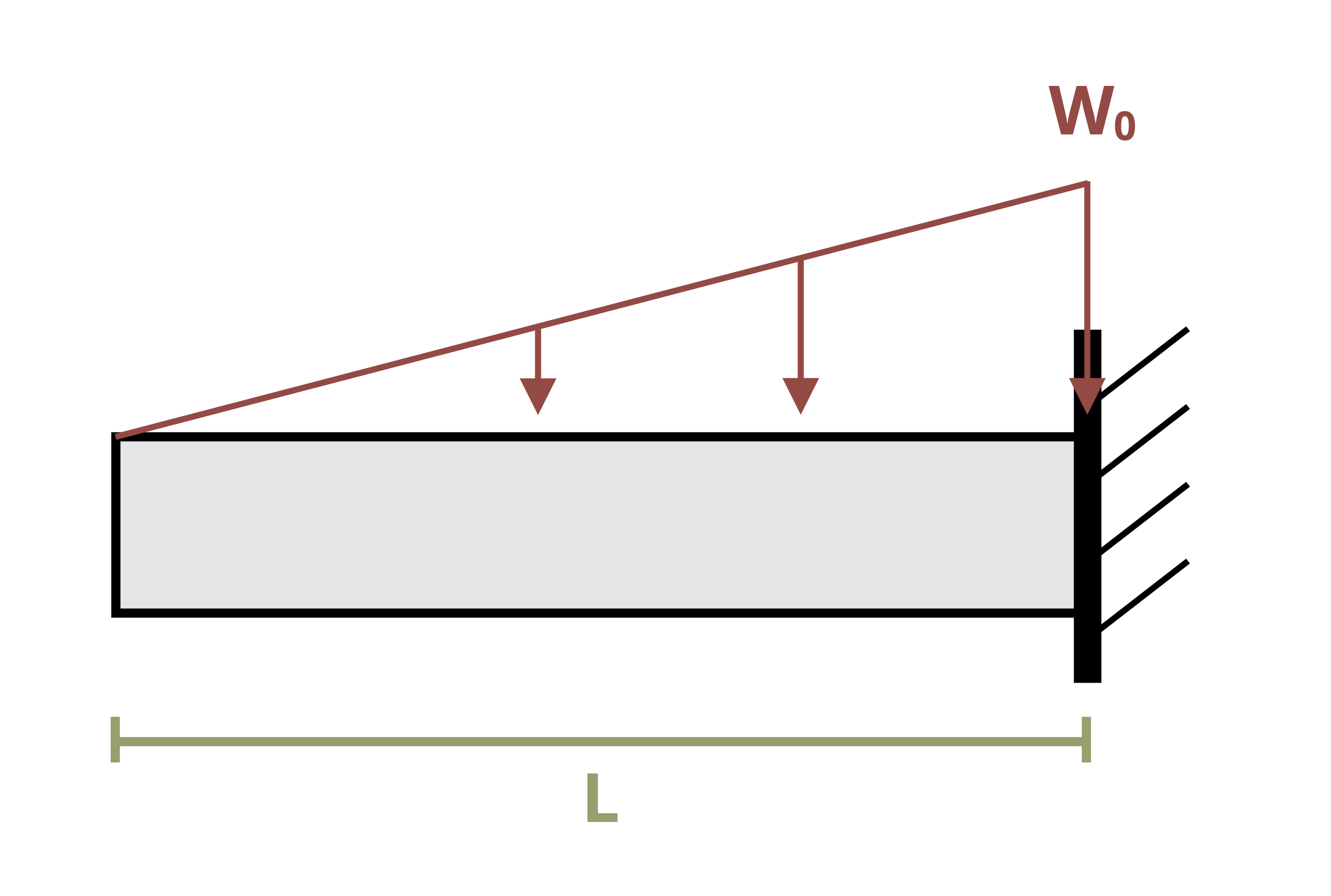

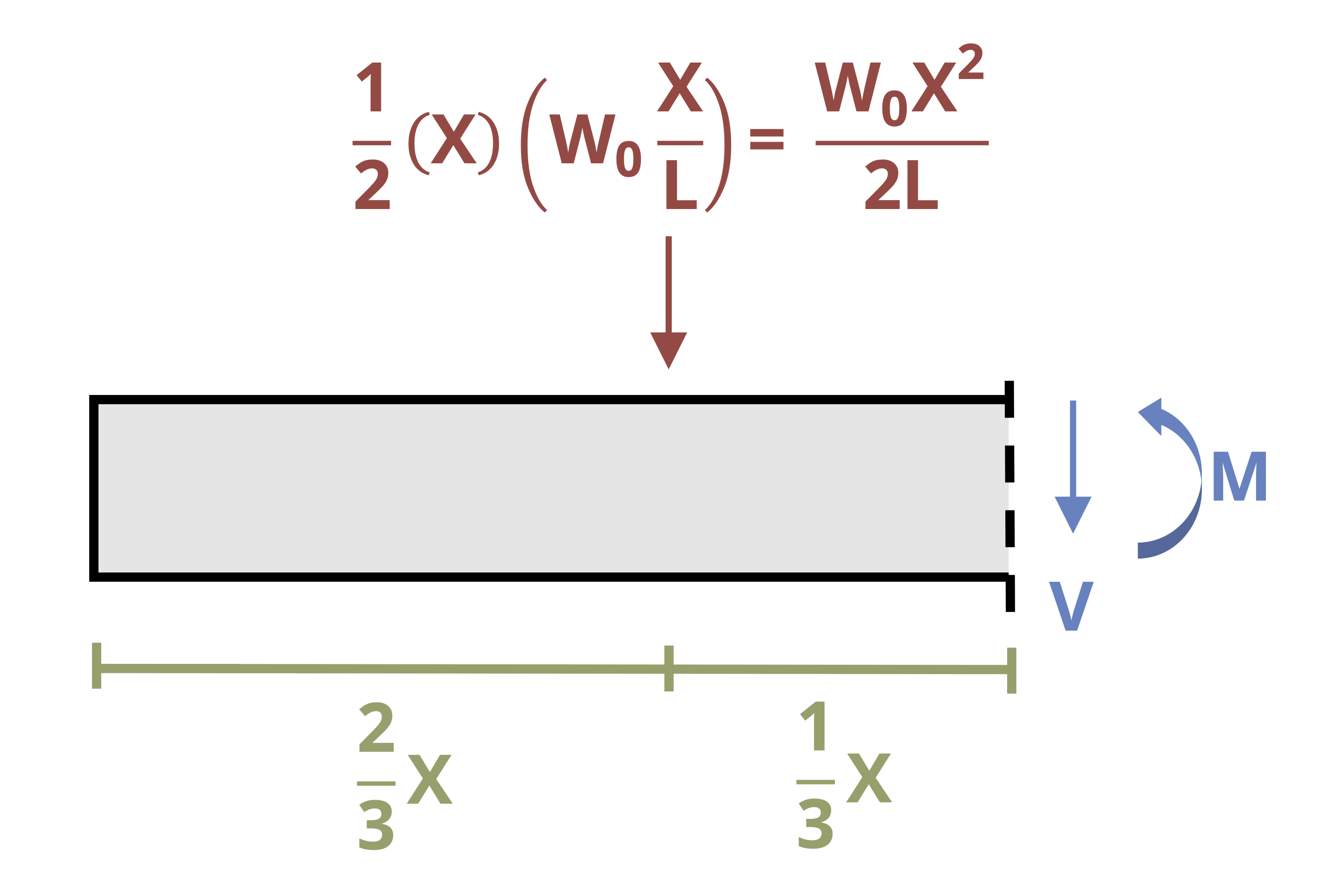

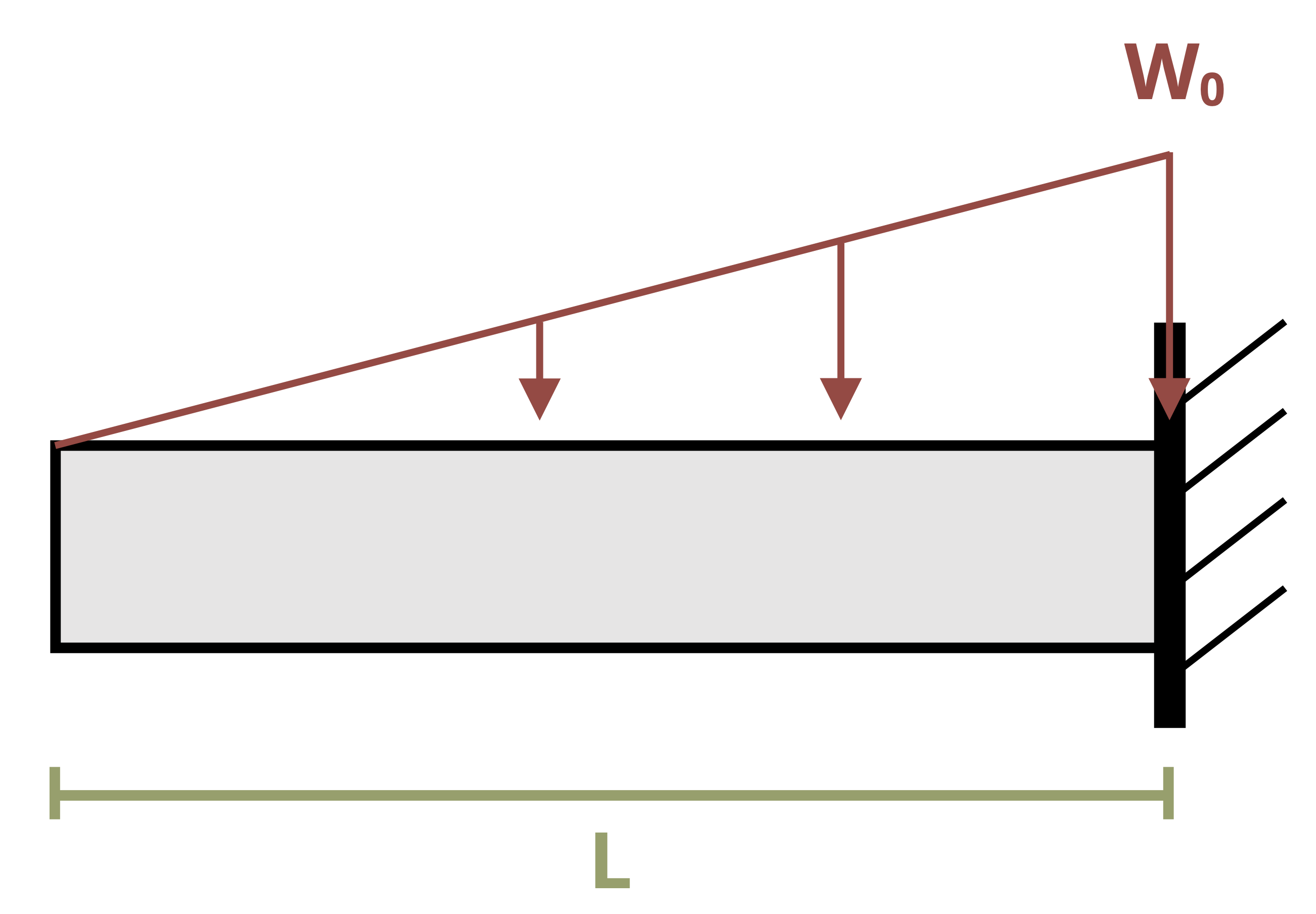

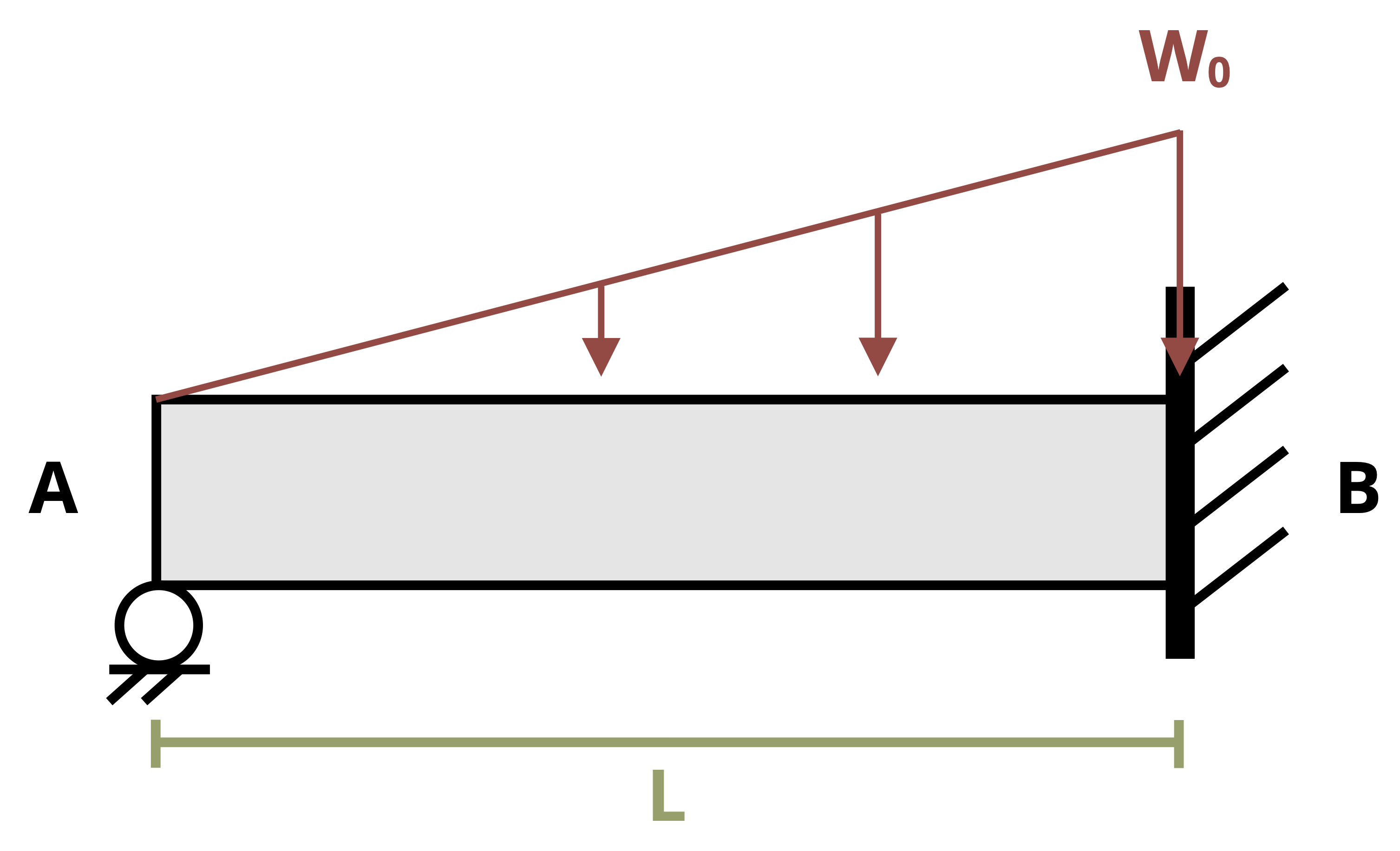

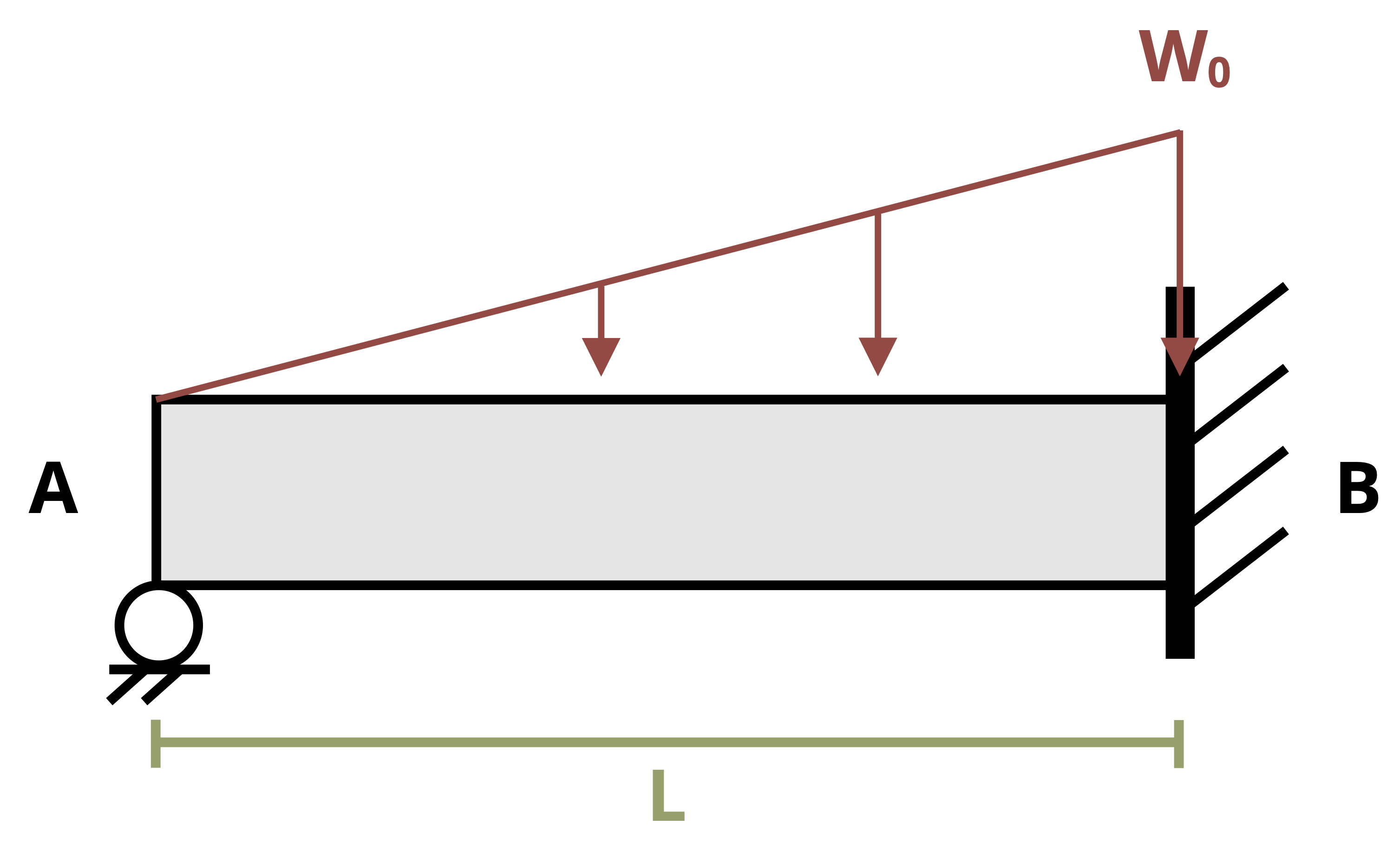

In the previous section we used equilibrium to determine the equation of the internal bending moment and integrated this equation twice. This approach works well for relatively simple loading such as concentrated loads and uniformly or linearly distributed loads. For more complex loads, such as that shown in Figure 11.7, determining the internal bending moment equation in this way can be difficult. However, it’s possible to avoid the need to do so.

In Section 11.1 we used equilibrium equations to determine the internal bending moment in a beam as a function of x. We related this bending moment to the deflection by

\[ M(x)=E I \frac{\partial ^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}} \]

In Section 7.2 we learned that there is a relationship between the internal bending moment, the internal shear force, and the external load. For an external distributed load, w, we found

\[ V=\int_{0}^{L} w(x) d x \]

\[ M=\int_{0}^{L} V(x) d x \]

We may therefore relate the deflection of a beam not only the internal bending moment but also to the internal shear force and external distributed load through successive integrations. For some loading configurations it can be simpler to integrate the distributed load equation four times instead of finding the equation of the internal bending moment through equilibrium and integrating twice. When taking the simpler approach, remember that loads acting downward (as most loads on beams do) are negative.

\[ \boxed{\begin{aligned} &w(x)=E I \frac{\partial^{4} y}{\partial x^{4}} \\ &V(x)=E I \frac{\partial^{3} y}{\partial x^{3}}=\int w(x)~dx+C_1 \\ &M(x)=E I \frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}}=\int V(x)~dx+C_2 \\ &EI\theta(x)=E I \frac{\partial y}{\partial x}=\int M(x)~dx+C_3 \\ &EIy(x)=\int \theta(x)~dx+C_4 \end{aligned}} \tag{11.2}\]

Note that each successive integral will introduce a new constant of integration. To solve for these constants we must again apply boundary conditions. Now with four constants four boundary conditions are required. Two of these conditions are the same as those in Section 11.1:

At any support the deflection is 0.

At a fixed support both slope and deflection are zero.

The other two boundary conditions come from knowing the value of the shear force and bending moment at a point in the beam. Our work in Chapter 7 enables us to find them. Although we can use known values at any point in the beam, it is generally easiest to use the shear force and bending moment at x = 0. Note the two conditions at this point:

The shear force will be equal to the applied force (including a force applied by a support) if there is one, or zero otherwise.

The bending moment will be equal to the applied moment (including a moment applied by a fixed support) if there is one, or zero otherwise.

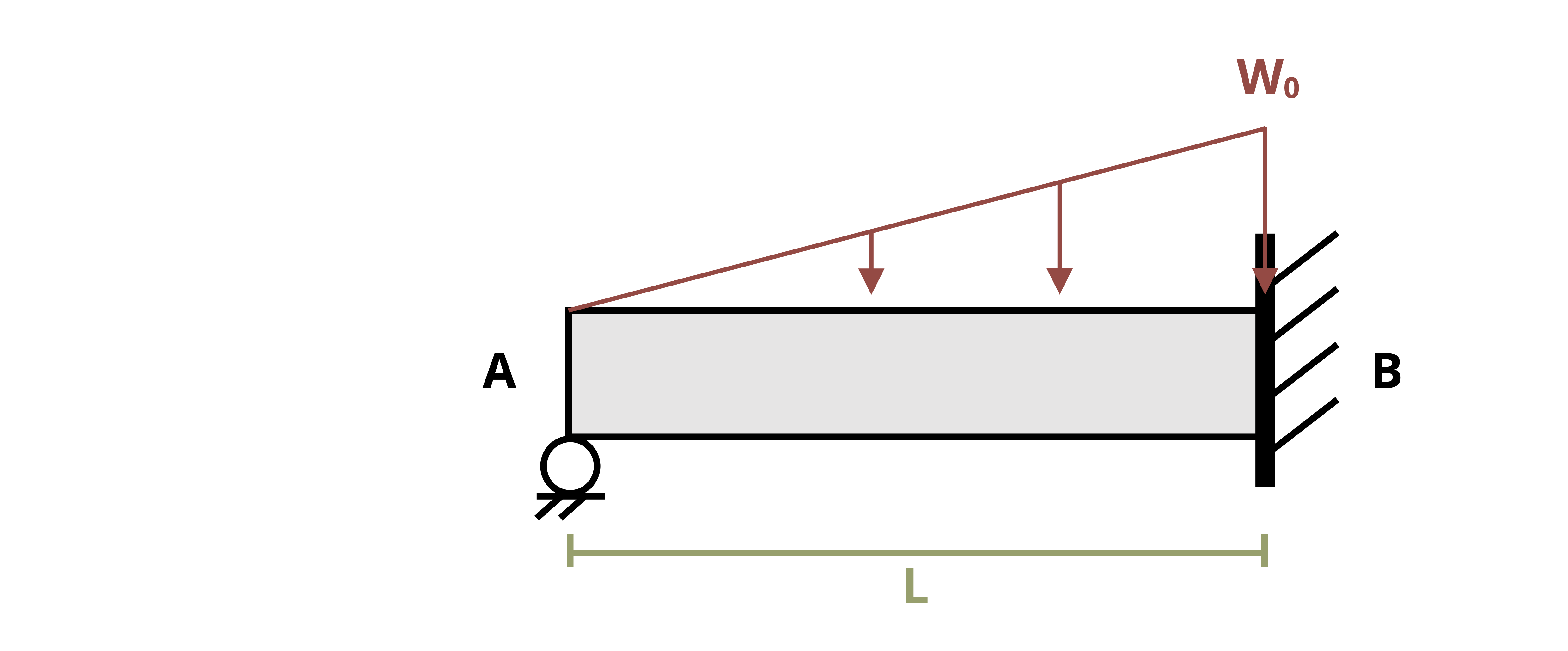

Example 11.4 demonstrates of how to find the deflection of a beam by integrating the load equation. Although this method can be used for any beam, it is best applied to beams with a single continuous distributed load acting over the length of the beam. Beams with discontinuous loading require integration of multiple load equations.

11.3 Superposition

Click to expand

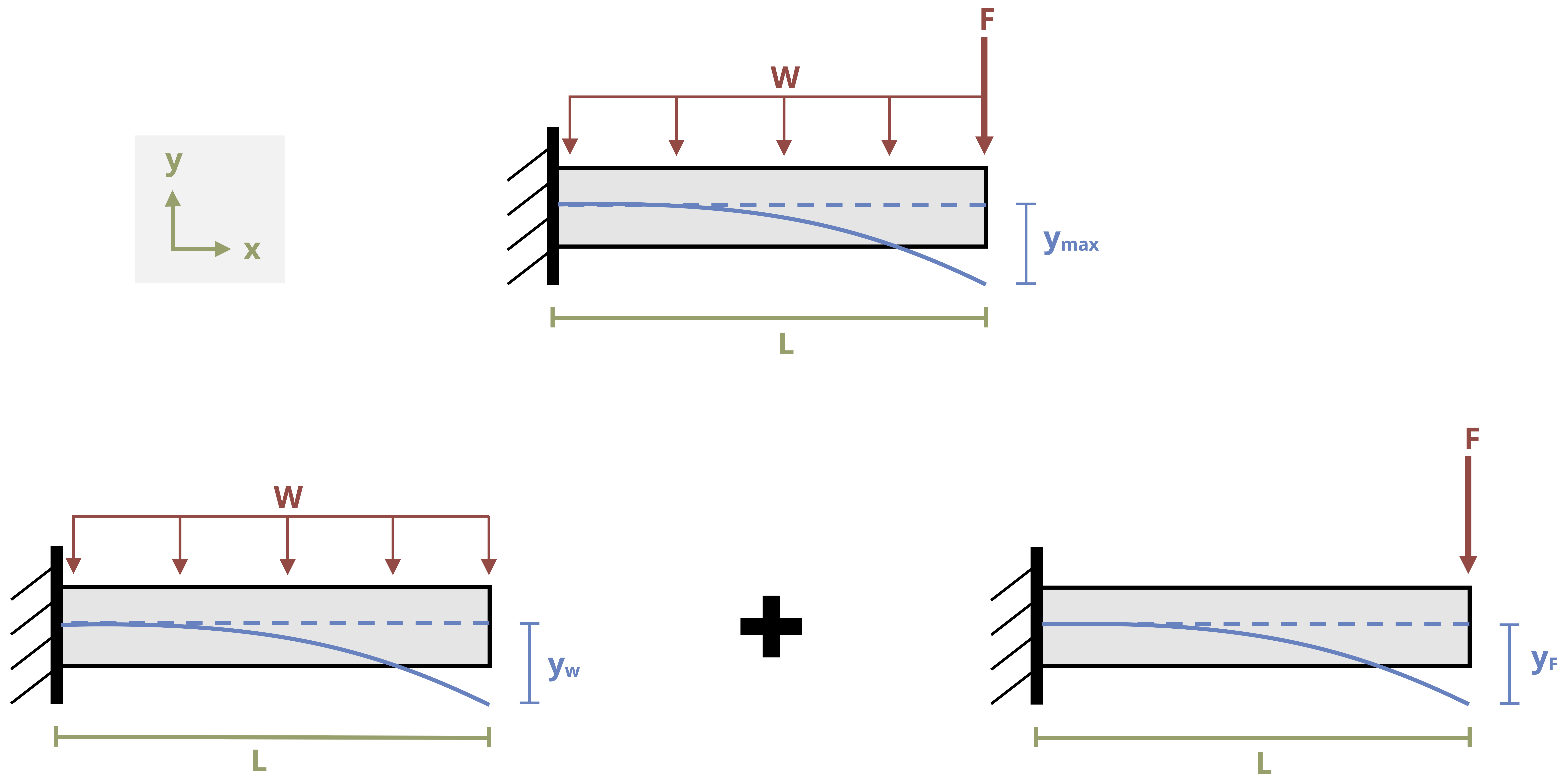

It should be apparent from the previous sections that finding deflection using the method of integration can become quite complicated and time-consuming if there are multiple loads. In such cases, the method of superposition is a good alternative.

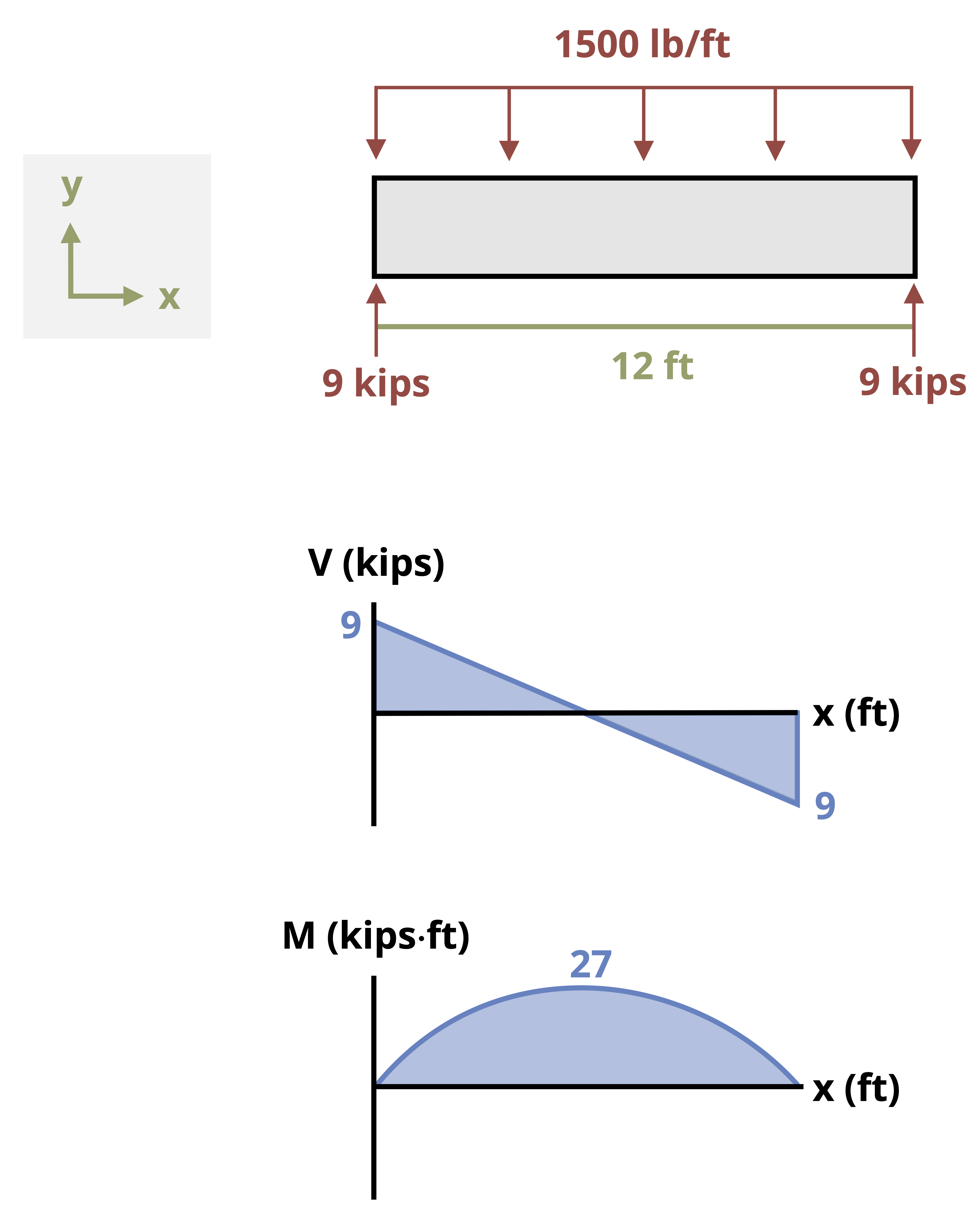

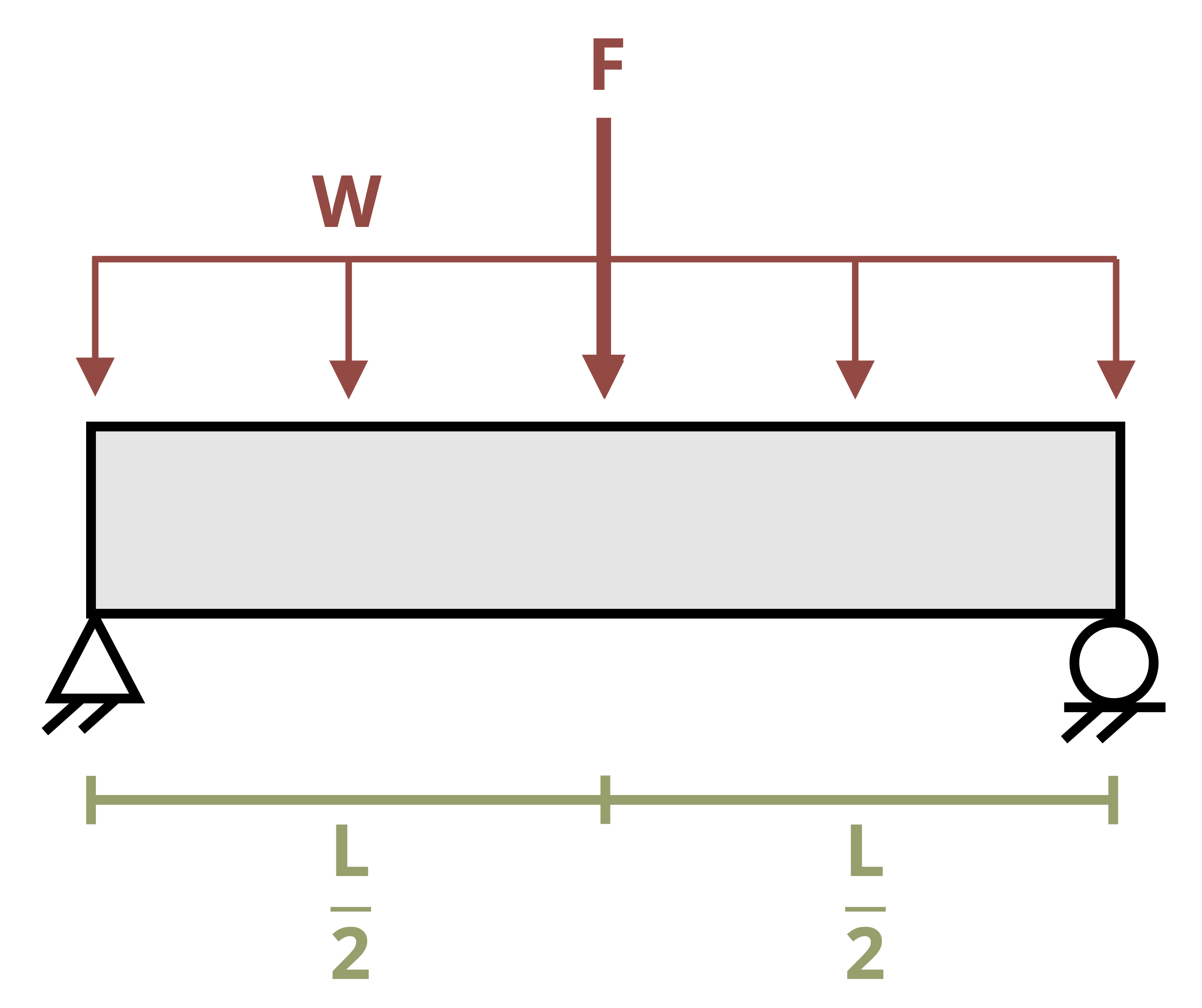

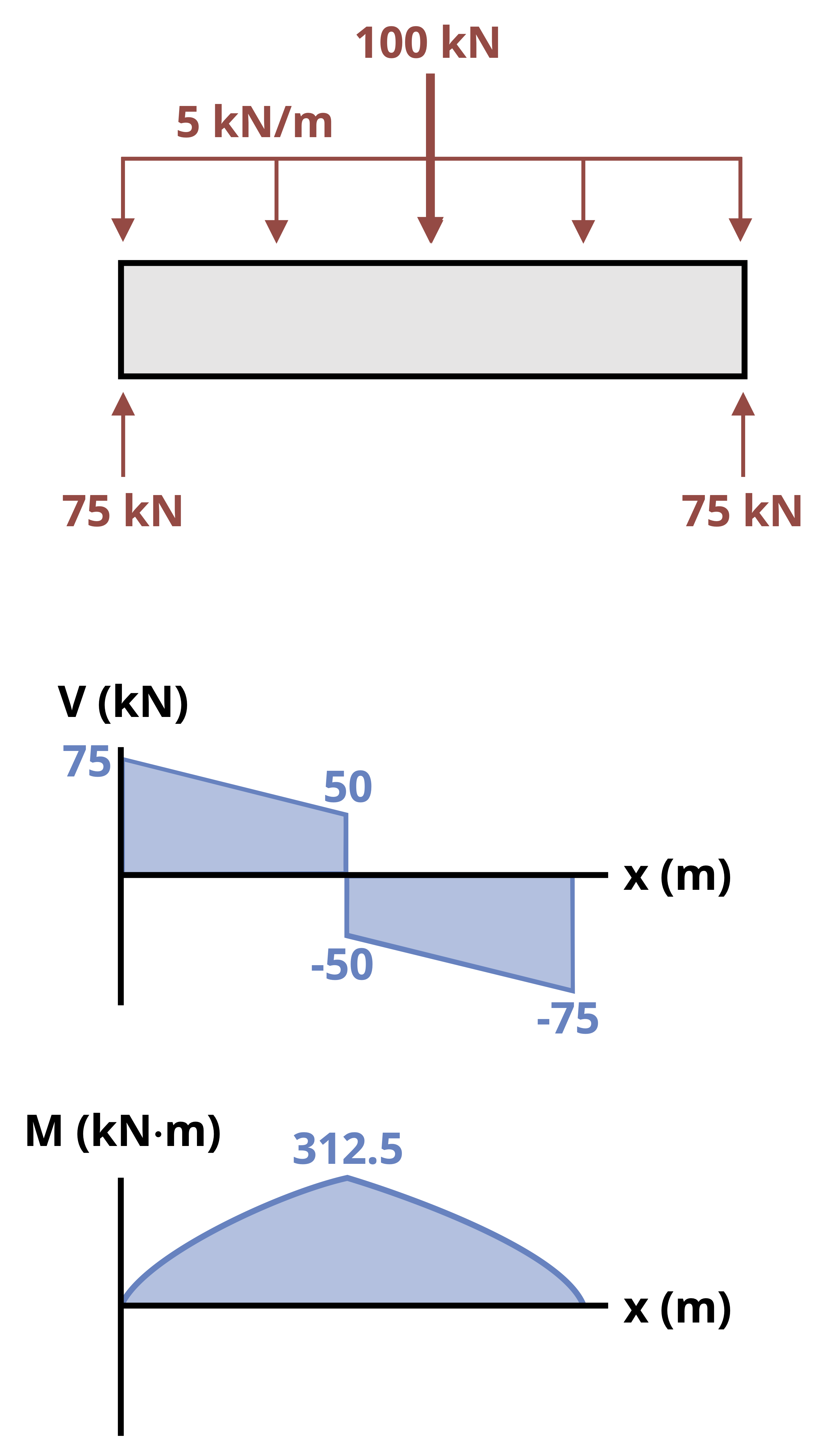

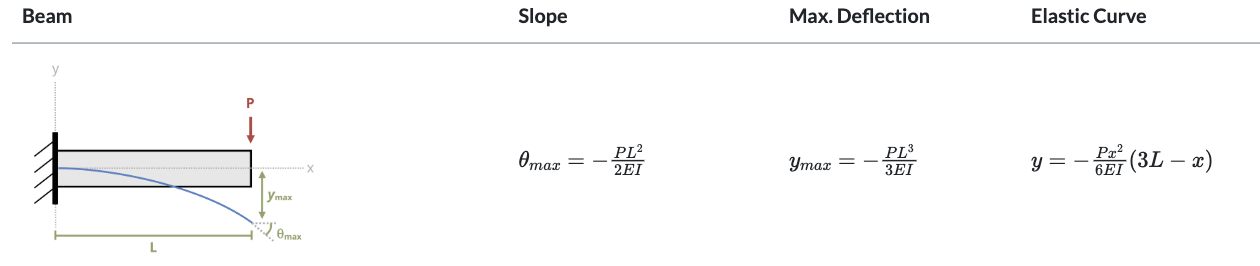

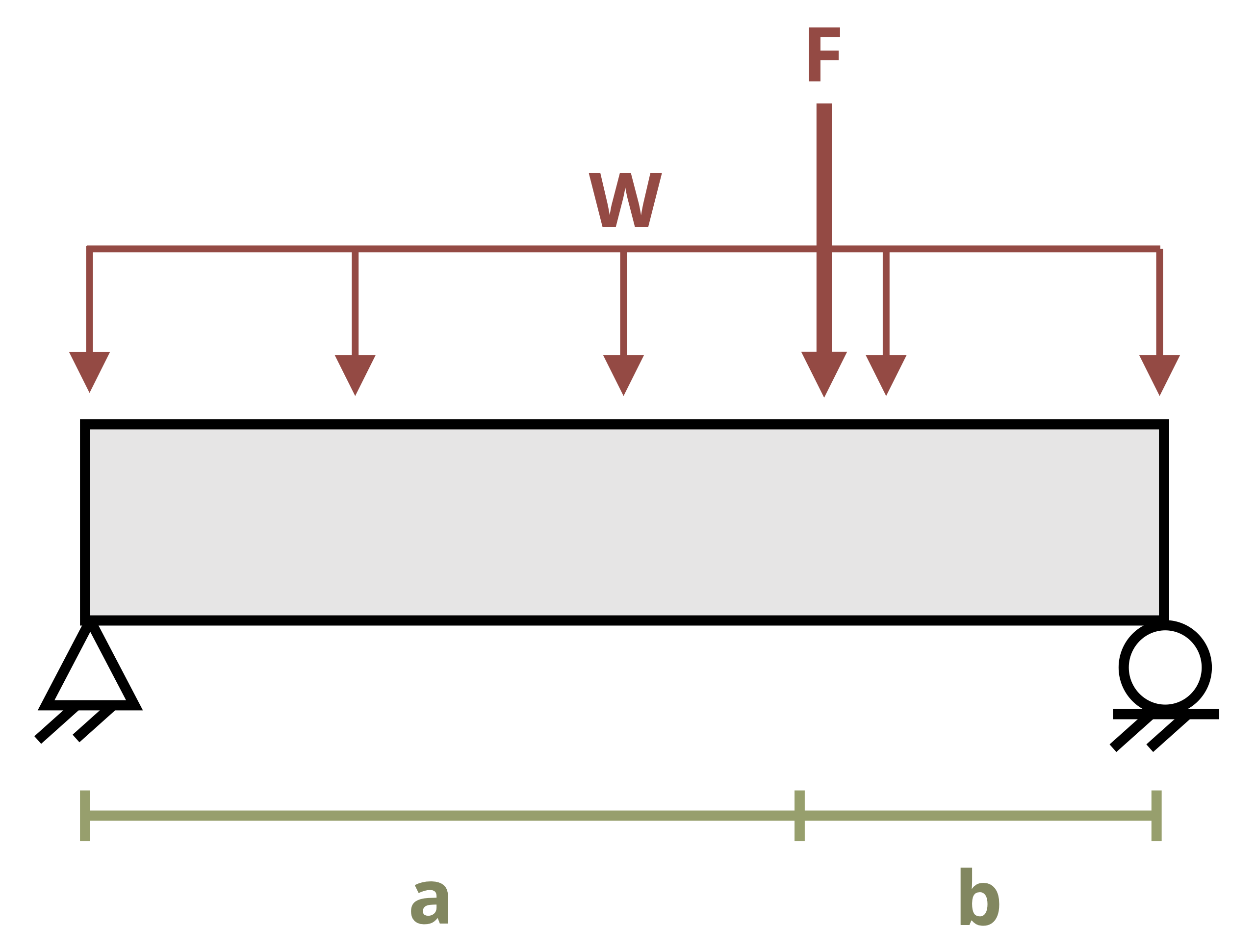

Beams are typically loaded in a relatively small number of standard configurations, and the deflection behavior of a beam subjected to one of these standard loads is very well understood. The slope and deflection equations for many common loading conditions have been derived through the methods described in Section 11.1 and Section 11.2 and recorded. A subset of these beam deflections has been included in Appendix B. Figure 11.8 shows an example of the information provided there for one such beam.

This information can be useful even for more complex loading. When multiple loads act on a beam, the effect of each load on the deflection of the beam may be considered independently. Thus even for loading more complex than the loads in Appendix B, it may be possible to simplify the problem by considering each load separately and calculating the deflection caused at a point by each load (Figure 11.9). These deflections can then be summed to find the overall deflection at that point. We must, of course, calculate the deflection at the same point for each load in order to add them together. See Example 11.5 for a demonstration.

\[ \begin{aligned} y_w = - \frac{wL^4}{8EI} \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad &\quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad y_F=-\frac{FL^3}{3EI} \\ y_{max}=-&\frac{wL^4}{8EI} - \frac{FL^3}{3EI} \end{aligned} \]

11.4 Statically Indeterminate Deflection

Click to expand

A problem is statically indeterminate if there are more unknown support reactions than there are equilibrium equations to solve for them. These problems were introduced in Section 5.5 and Section 6.3. In both sections, to solve statically indeterminate problems we took advantage of our knowledge of deformation to solve for one of the reaction forces before using equilibrium equations to find the others. We’ll do something similar here. We may use either an integration method like that used in Section 11.1 or a superposition method like that used in Section 11.3.

In practice engineers design structures with redundancies so that if one part fails it can be replaced without the entire structure collapsing. As such, static indeterminacy is the norm.

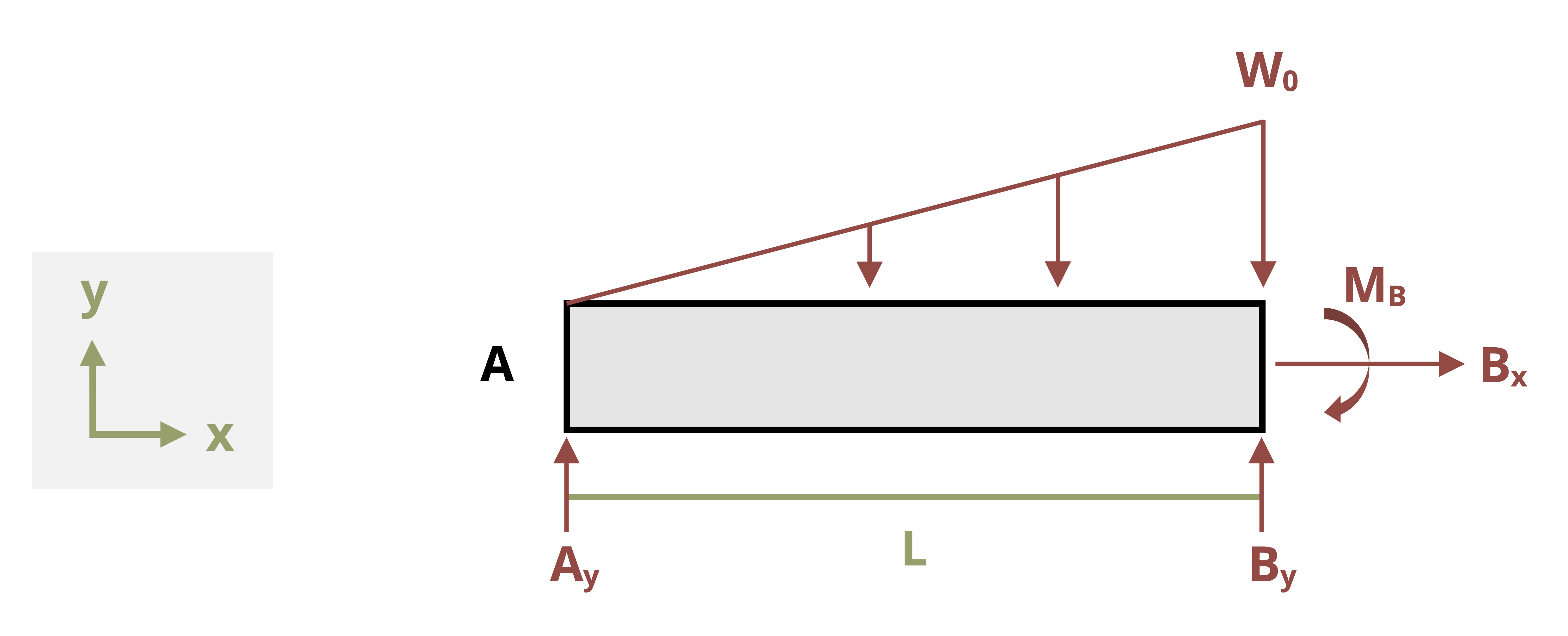

In Section 11.1 we cut a cross-section and found the internal bending moment as a function of x, M = f(x). This was integrated twice to determine the equation of the elastic curve. For statically indeterminate problems, we’ll write the moment equation as a function of both x and A, where A is the unknown force at the redundant support. Integrating this equation twice results in three unknowns, but also three boundary conditions. These unknowns and boundary conditions enable us to solve for the redundant reaction force, and then we can use equilibrium equations to solve for the other reactions. See Example 11.6.

This method works well for beams with a single continuous load. While it can be used for more complex loads, it quickly becomes complicated and time-consuming. For these cases superposition is recommended.

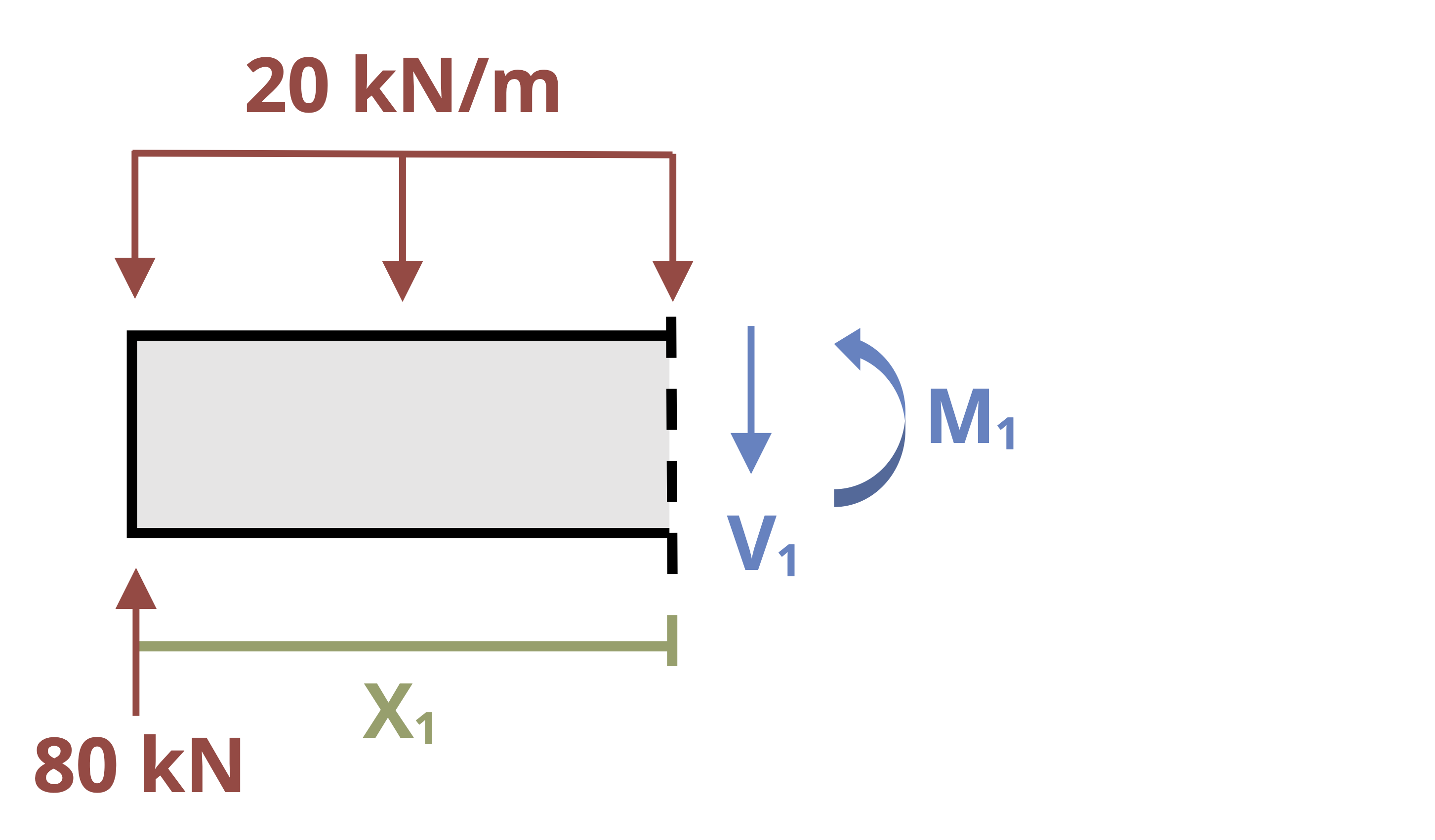

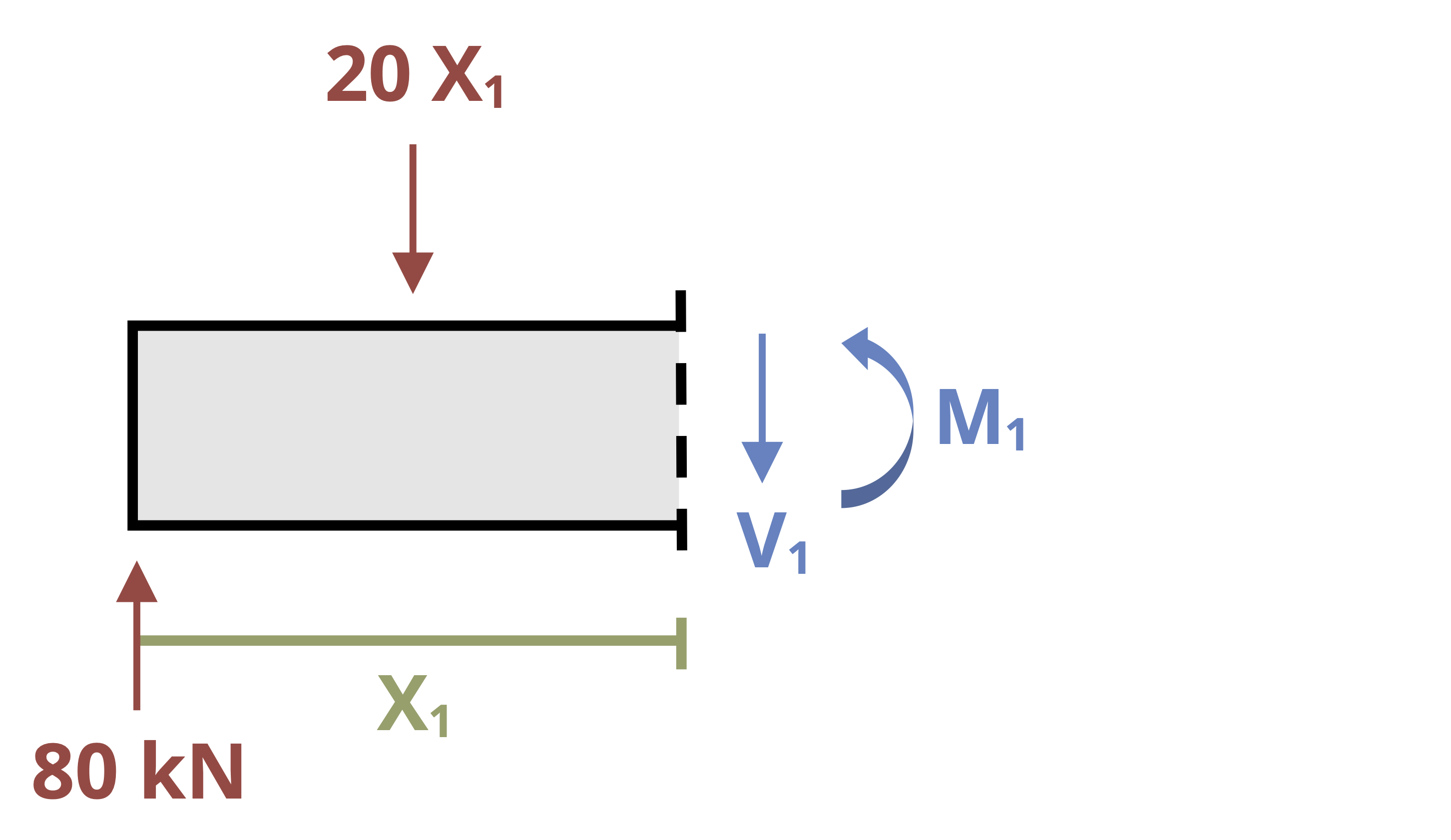

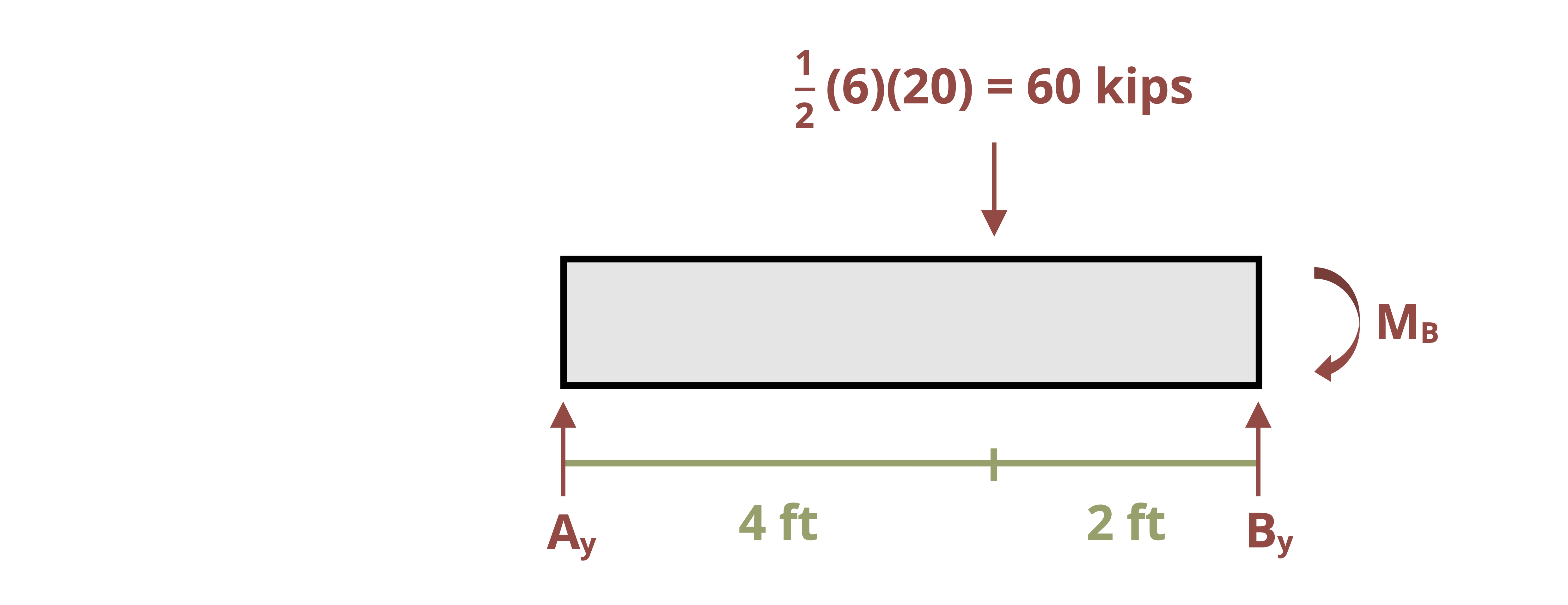

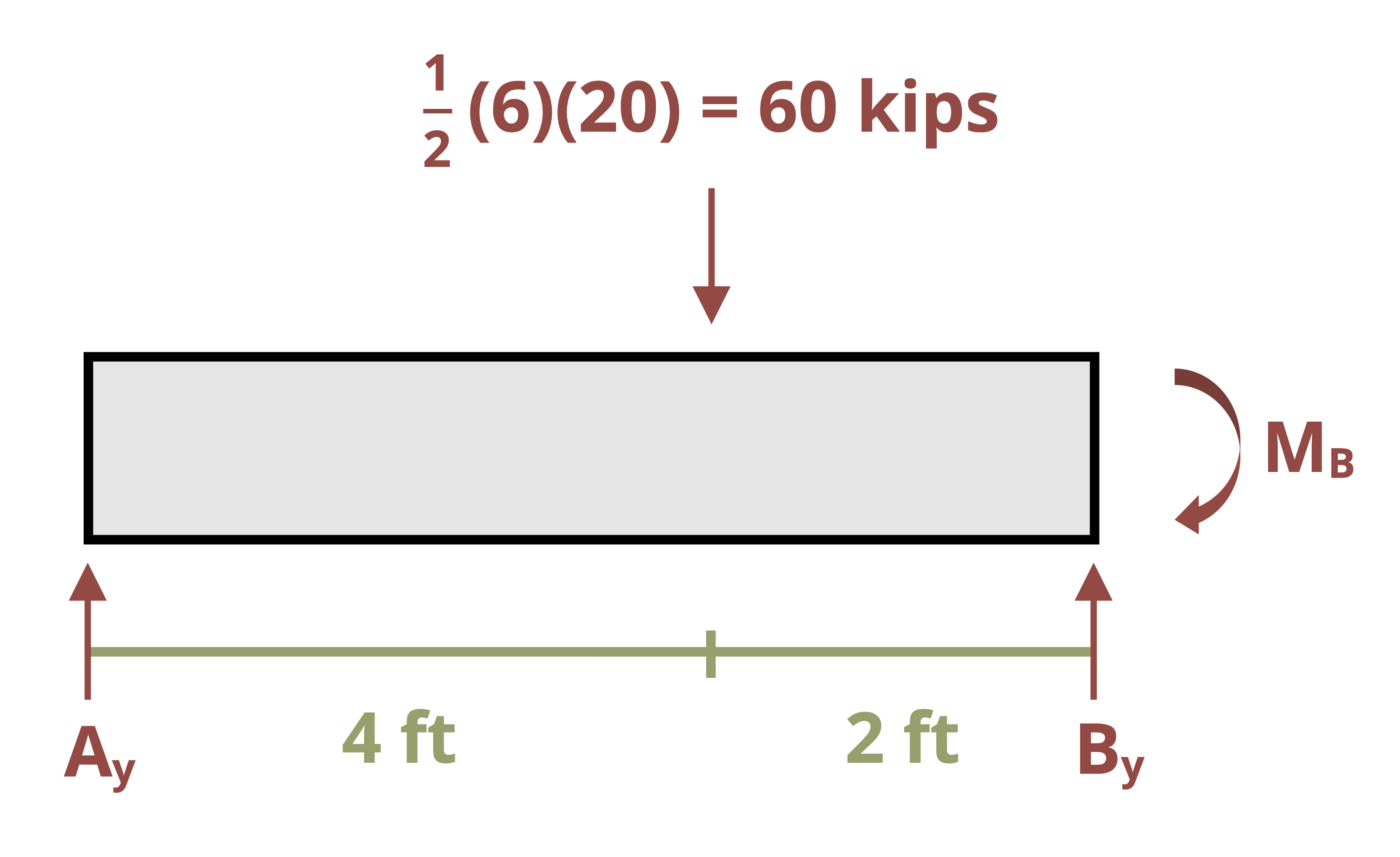

The superposition method is like the methods used to solve other statically indeterminate problems in Section 5.5 and Section 6.3. To solve a statically indeterminate deflection problem using superposition, first identify the redundant support. We have three equilibrium equations and so can solve for three unknown support reactions. Any support reactions beyond these three are redundant.

Remove each redundant reaction and determine the deflection resulting from the applied loads at the point where the reaction was removed. Without fail do this for each redundant reaction. It is best to remove a support such that the remaining beam is either simply supported or cantilever, given that these are the only support configuration in Appendix B.

Then replace each redundant reaction and determine the resulting deflection where the reaction is applied. Since there is actually a support here, the total deflection must be zero. Sum both deflections and set them equal to zero. This enables you to calculate the value of the redundant support. Once this is known, the other reaction loads can be determined using equilibrium. See Example 11.7 for a demonstration.

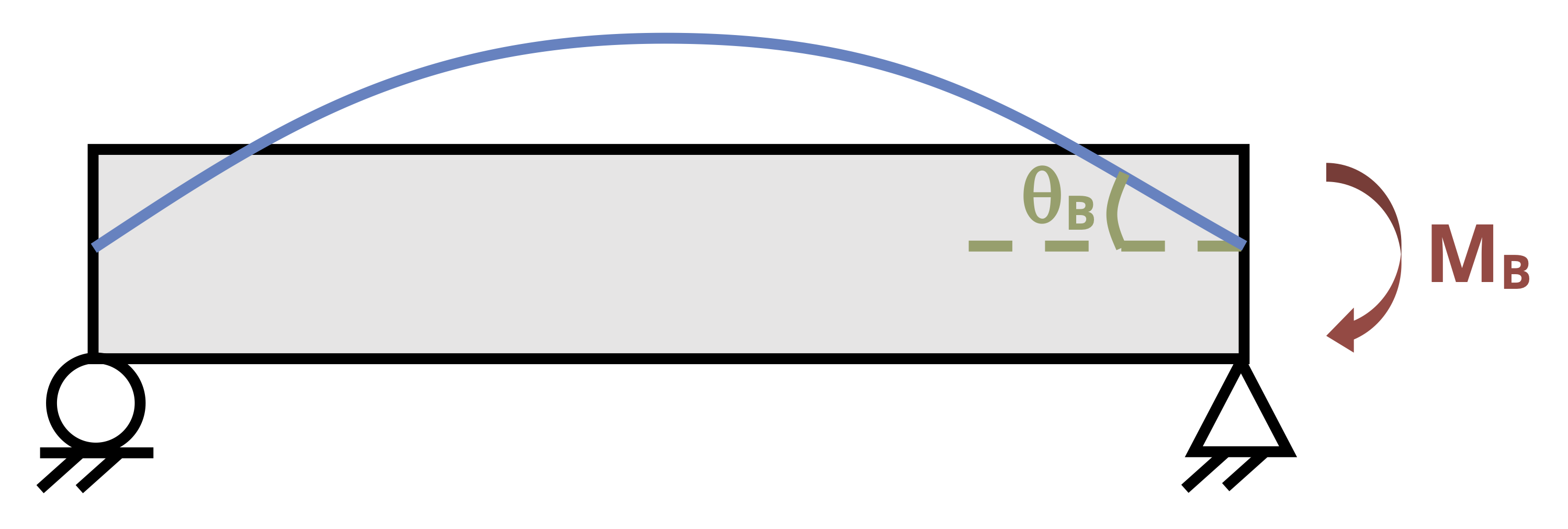

It’s possible to remove a moment reaction so that what remains is a simply supported beam. In this case, determining the deflection at the point where the load was removed isn’t helpful because removing the moment reaction from a fixed support effectively leaves a pin support and the deflection with the moment removed will still be zero. In this situation look at the slope at the point where the reaction was removed.

Example 11.7 is repeated with the moment at B removed instead of the force at A.

Note that some problems may involve multiple redundant reactions. In such cases remove all redundant reactions and determine the deflection from the external loads at every point where a reaction was removed. Then replace the redundant reactions one at a time and determine the deflection from each load at every point where a reaction was removed. As before, the total deflection at each of these points must be zero. Sum the deflection at each point and set it equal to zero. There will be one equation for every redundant reaction, and so all redundant reactions can be calculated.

11.5 Beam Design for Bending, Shear, and Deflection

Click to expand

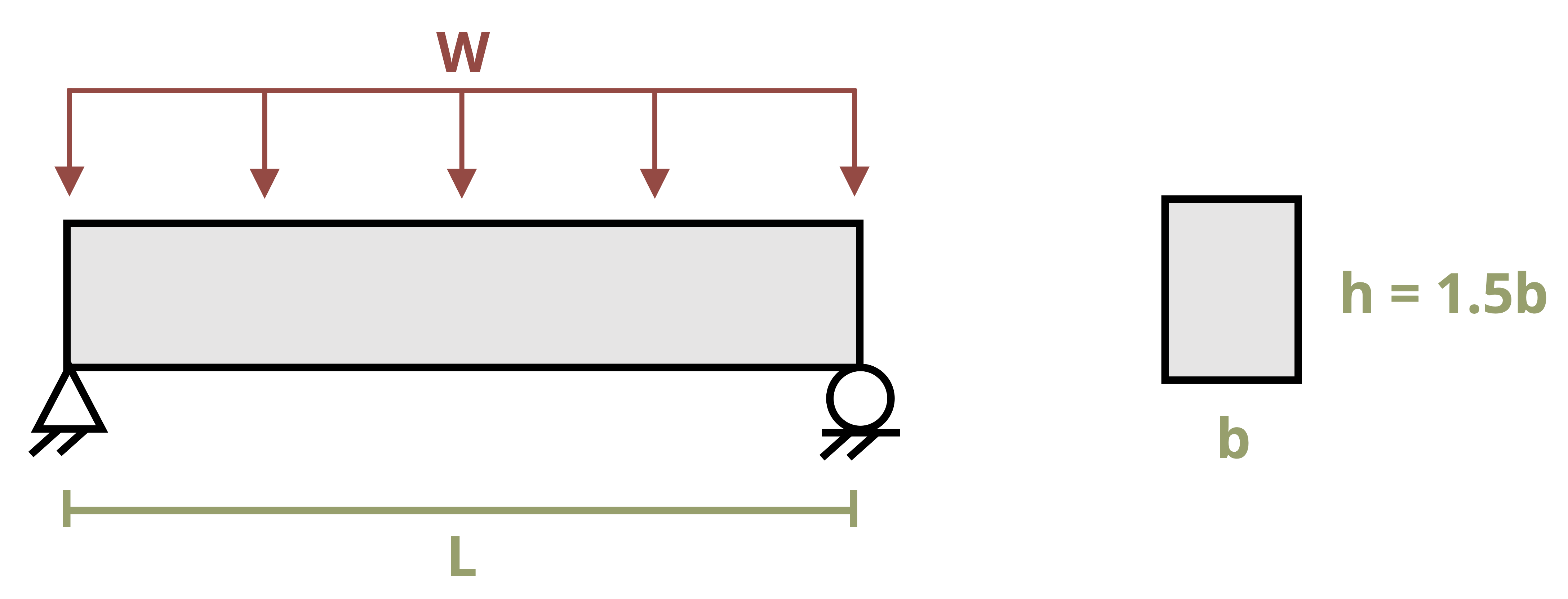

Section 9.2 showed us how to use the section modulus to design a beam to meet bending stress specifications. In practice, beams must also meet specifications for shear stress and deflection. Limitations are placed on all three of these criteria, and we must design our beams to meet all three simultaneously. We’ll begin with rectangular cross-sections and then move on to standard beams using Appendix A.

As in Section 9.2, problems involving rectangular cross-sections typically relate the base and height of the cross-section such that only one dimension must be determined. Previously we designed the cross-section to resist bending stress using

\[ S_{\min }=\frac{M_{\max }}{\sigma_{allow}}=\frac{I}{c} \]

Since \(I=\frac{b h^{3}}{12}\) and \(c=\frac{h}{2}\), we were able to determine the required dimensions to meet the minimum required section modulus. Note that the equation \(S=\frac{I}{c}\) simplifies to \(S=\frac{\frac{b h^{3}}{12}}{\frac{h}{2}}=\frac{2 b h^{3}}{12 h}=\frac{b h^{2}}{6}\) for a rectangle.

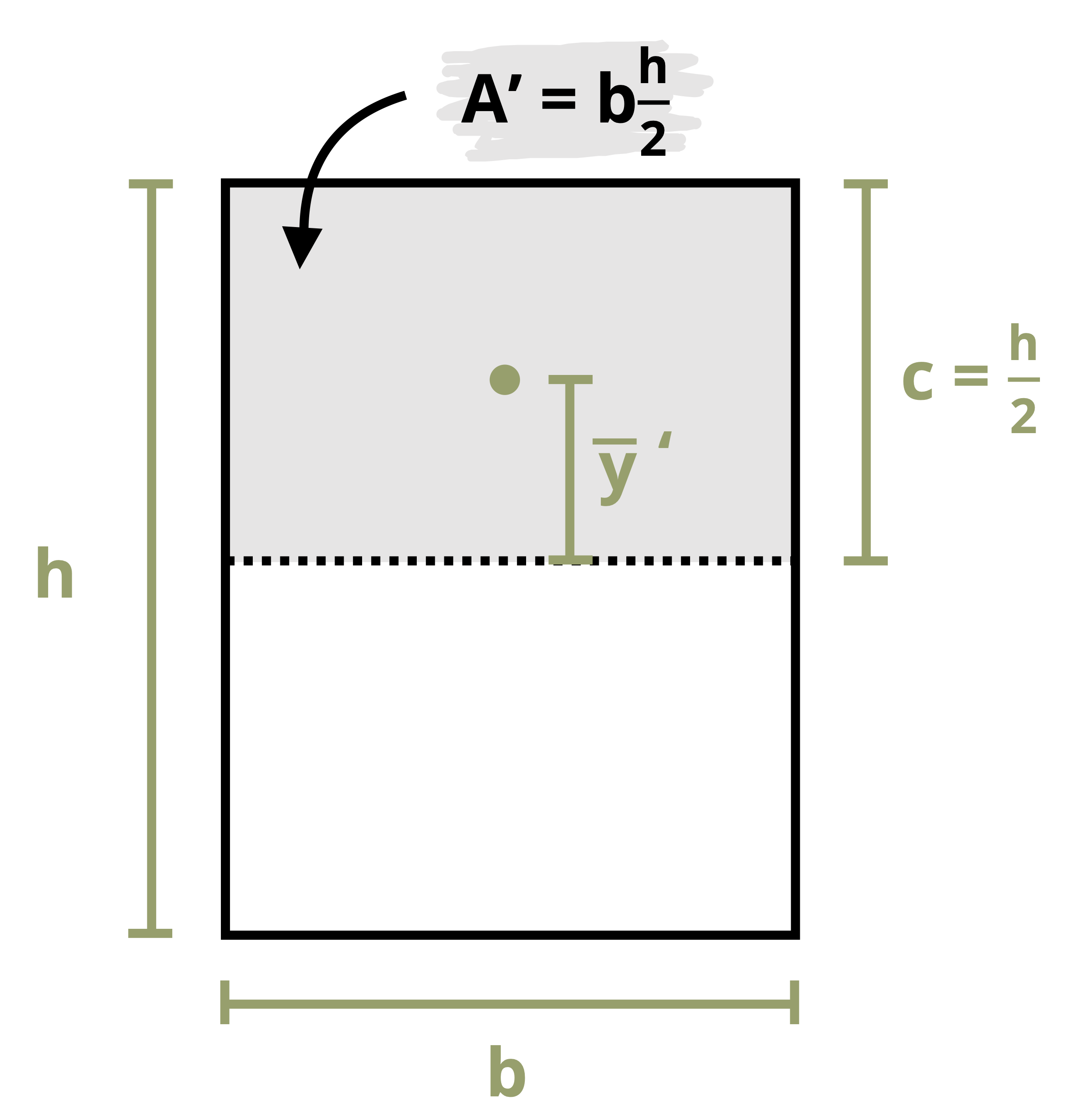

To meet the minimum required shear stress, use \(\tau=\frac{V Q}{I t}\). Applying the method of Section 10.1, to a rectangle (Figure 11.10) shows that \(Q=y A=\frac{h}{4} \frac{b h}{2}=\frac{b h^{2}}{8}\).

With \(I=\frac{b h^{3}}{12}\) and \(\mathrm{t}=\mathrm{b}\), rewrite the shear stress equation to find the maximum shear stress in a rectangular cross-section as \(\tau_{\max }=\frac{V \frac{b h^{2}}{8}}{\frac{b h^{3}}{12} b}=\frac{12 V b h^{2}}{8 b^{2} h^{3}}=\frac{12 V}{8 b h}=\frac{3}{2} \frac{V}{A}\).

Thus set \(\tau_{\max }=\frac{3}{2} \frac{V}{A}\) and solve for the required dimensions to not exceed the maximum allowable shear stress.

The maximum deflection of the beam under a given loading configuration can be found using the methods shown in this chapter. Wherever possible use superposition and Appendix B. If it’s not possible to do so, then use the method of integration instead. In either case the equation for the beam’s maximum deflection will include the second moment of area, I. Set the maximum allowable deflection equal to this equation and replace \(I=\frac{b h^{3}}{12}\).

Then solve for the cross-section’s required dimensions to not exceed the maximum allowable deflection of the beam.

You now have three different dimensions: one required to not exceed the maximum bending stress, one required to not exceed the maximum shear stress, and one required to not exceed the maximum deflection. Since none of these limitations may be exceeded, select the largest of the three potential answers. See Example 11.8 for a demonstration.

For standard beams again use the method of Section 9.2 to select a beam from Appendix A that meets the specifications for bending stress. Use \(S_{\min }=\frac{M_{\max }}{\sigma_{allow}}\) and select a beam with \(\mathrm{S}>\mathrm{S}_{\min }\).

Next determine the equation for the beam’s maximum deflection under the given loading conditions. As before, use superposition and Appendix B whenever possible. Set the maximum allowable deflection equal to this equation and solve for the minimum required second moment of area, \(I_{\min }\). Now select the lightest beam from Appendix A that meets both \(S_{\min }\) and \(I_{\min }\).

Steel W beams rarely fail from shear stress, but shear must nonetheless be checked. An exact value for the maximum shear stress in the beam can be found from \(\tau_{\max }=\frac{V Q}{I t}\). However, the beam’s web resists most of the shear stress. A reasonable estimate of the maximum shear stress can be found using \(\tau_{estimate}=\frac{V}{A_{web}}\). This calculation is relatively simple, but it’s important to note that it is only an estimate. In most cases the maximum shear stress will be significantly less than the allowable shear stress, and this estimate will suffice to demonstrate that. In the rare case that the maximum shear stress is within 20 percent of the allowable shear stress, an exact value must be determined using \(\tau_{\max }=\frac{V Q}{I t}\).

The beam was selected to meet the bending stress and deflection requirements. As long as the maximum shear stress is less than the allowable shear stress, the beam can be used. See Example 11.9 for a demonstration.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

- Figure 11.1: A model bridge showing severe deflection along its span (left). Left: Denise Krebs. 2012. CC BY. https://flic.kr/p/bnc8qp. Right: clyde. 2012. CC BY-NC. https://flic.kr/p/bpkcyR.

part 1.png)

part 2.png)

_last figure.png)